Serhii Zabohonskyi

Serhii was born in Horlivka, Donetsk Oblast, and later moved to Mariupol. At the time of the attack, Serhii had been working as an actor for the Mariupol Drama Theater for almost 20 years. His wife, the theater’s lighting director Yevheniia Zabohonska, is also one of our witnesses.

At the end of February, as Russia's war against Ukraine intensified and the city came under heavy bombardment, Serhii headed to the Drama Theater, where his wife and daughter had already sought refuge. As the number of people arriving at the theater increased, Serhii and Yevheniia took charge of organizing the theater’s volunteer group and coordinating the activities of over 2,000 people who had gathered there.

On 16 March 2022, during the Russian Federation army's attack on the Drama Theater, Serhii and his wife were in the electrical workshop on the theater's stage, just a stone's throw from the explosion's epicenter. After being trapped under the rubble, they managed to escape and eventually evacuated from Mariupol.

During the interview, Serhii described how the theater became a shelter and how life was organized inside through the efforts of the volunteer group. He also recounted his experiences during the attack on the building.

These are selected fragments of an in-depth interview with Serhii, supplemented by visualizations, photos, and plans that describe the transformation of the theater’s spaces during the siege of Mariupol.

Serhii’s tasks in the theater during the siege

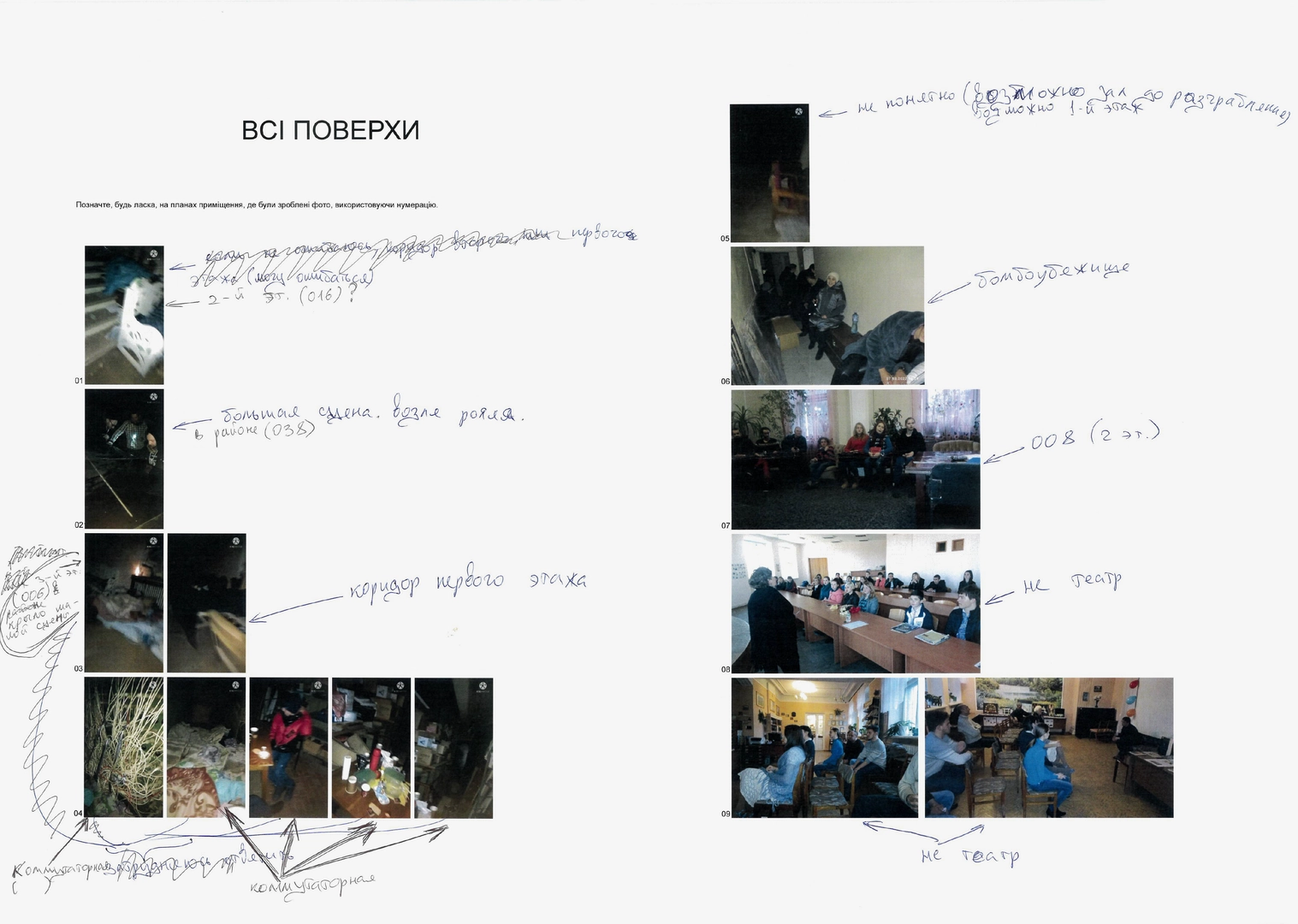

My main tasks were, let’s say, to provide food and to carry out “public relations”.1 At the beginning of the war, some people brought and cooked their own food. I focused on finding bread and water. I also kept the police and volunteer organizations informed about our situation. Once they learned that 700 of us were sheltering in the theater, the police and volunteers began to supply us with food.

Every morning and every evening, I would walk through all the floors and ask how people were feeling. During the day, I would go through all these spaces to see what was missing. In dressing room 34, there was a first-aid post. I would go there to find out what medications were needed. Then I went to the Red Cross or other organizations that were helping us. That’s how I tried to get what I needed.

Essentials and interaction with other shelters

We were in need of everything. From time to time, volunteers brought different things. They carried flashlights, matches, candles, baby food, medicines, hygiene products—whatever they could get. They collected information from the shelters and allocated resources that way. For example, if there were a lot of cookies in one shelter, they would bring them to a shelter that didn’t have enough, and vice versa, but it wasn’t centralized.

As more and more people appeared in the theater, we needed the proper utensils. We needed pots, knives, and other items for the kitchen. I asked the police for permission to open the “One Gogi” restaurant in the square, literally 30 meters from the Drama Theater. We explained that we weren’t going to loot. The police officer allowed us to open the restaurant and we could take the pots. At that time, the owner of the “One Gogi” arrived and said, “Guys, take whatever you need.”

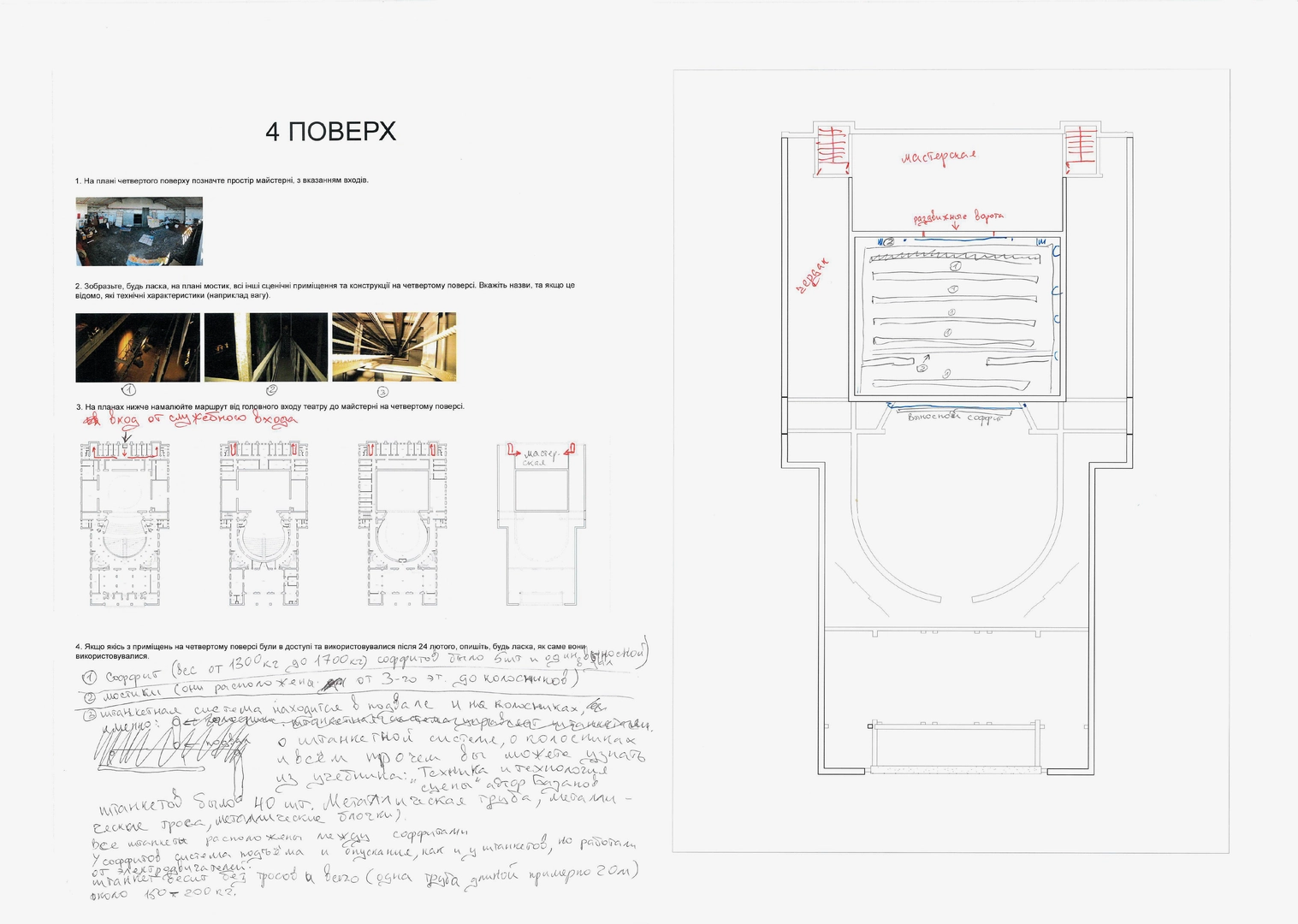

Media (a fragment of the construction of the electrical workshop)

The police officers gave my wife cigarettes and some alcohol so that we could exchange them for basic necessities. Together with other scarce things and foodstuffs, we stored them in the electrical workshop behind the stage in the theater. We also stored drinking water, baby food, matches, flashlights, and batteries there. This room was locked with a key, and only my wife had the key, as she worked there as a lighting technician in the theater.

In the first days after February 24, she and our daughter lived in this room: they made mattresses on the floor and slept dressed. So the space was transformed from an electrical workshop into a warehouse and a place to sleep.

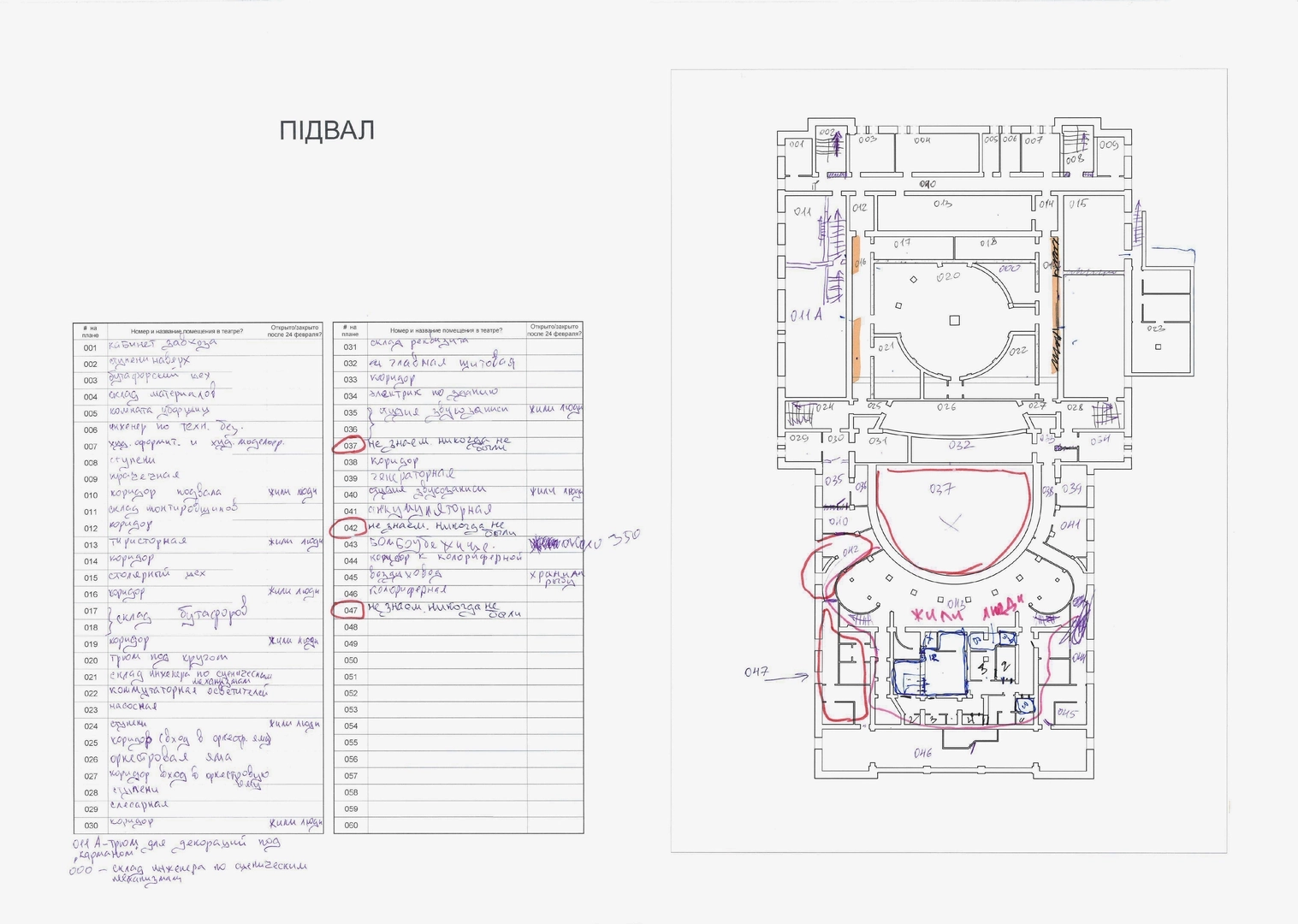

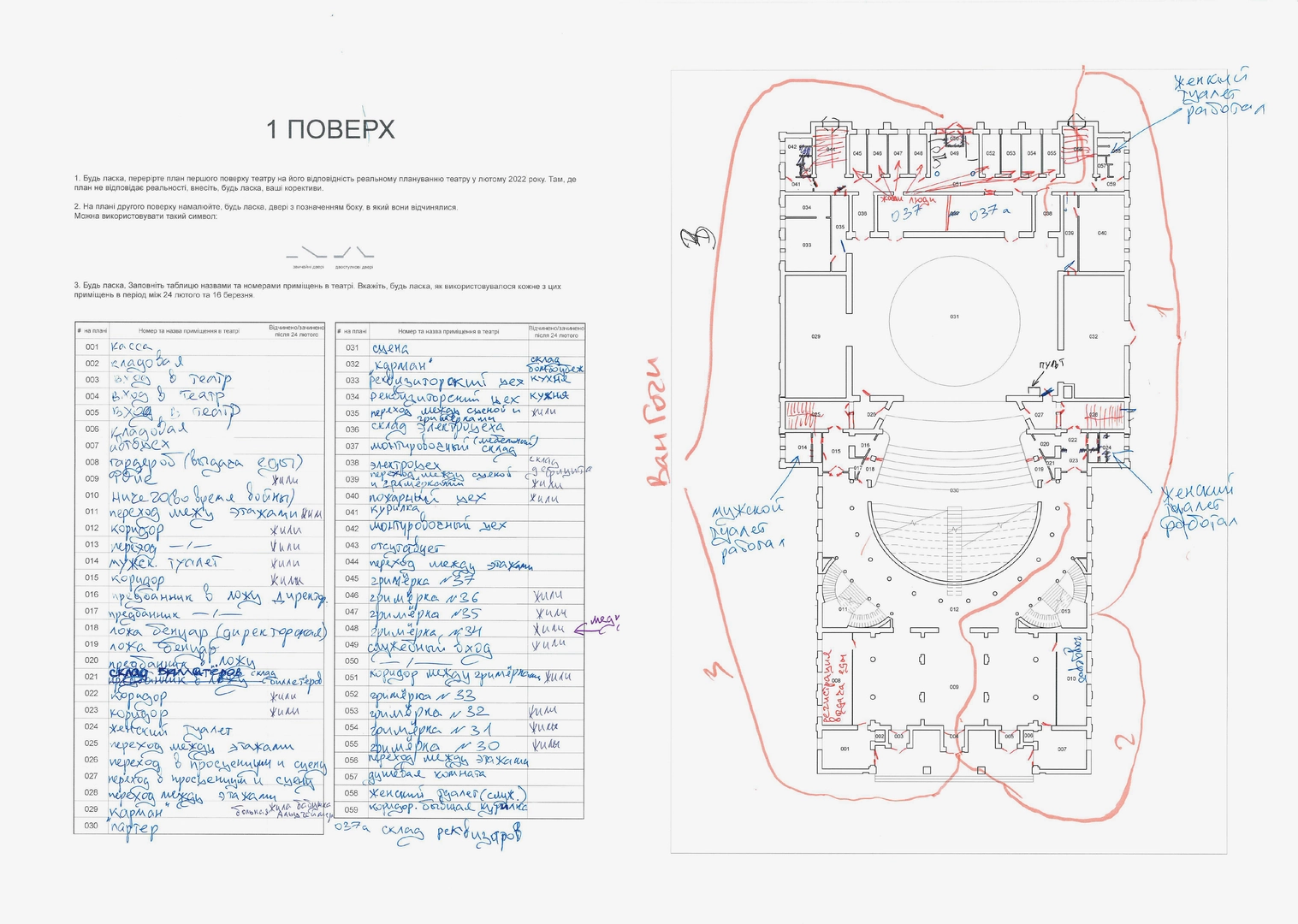

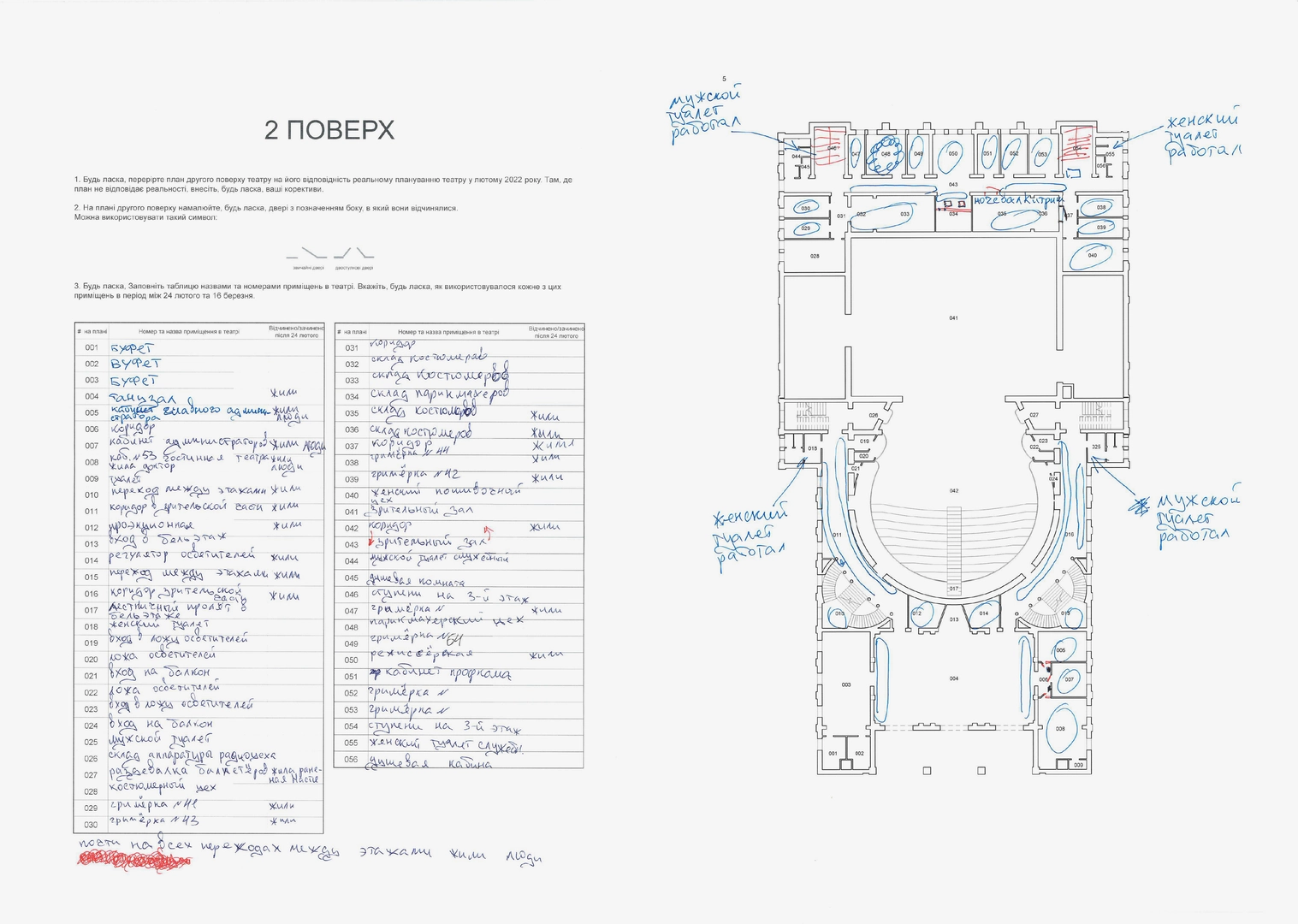

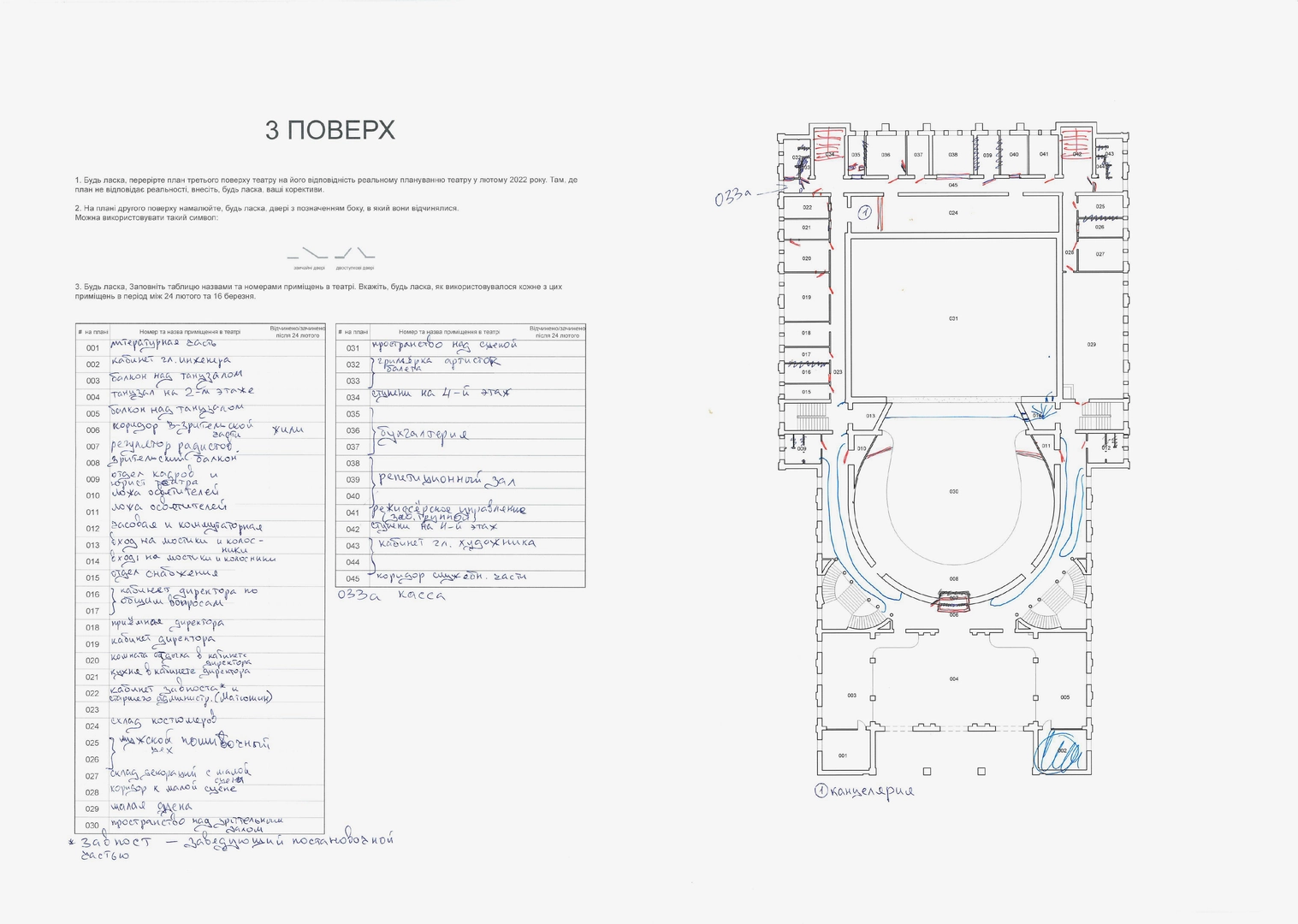

Serhii marked the changes in functions in different theater rooms and the spaces where people lived. We have added these drawings below.

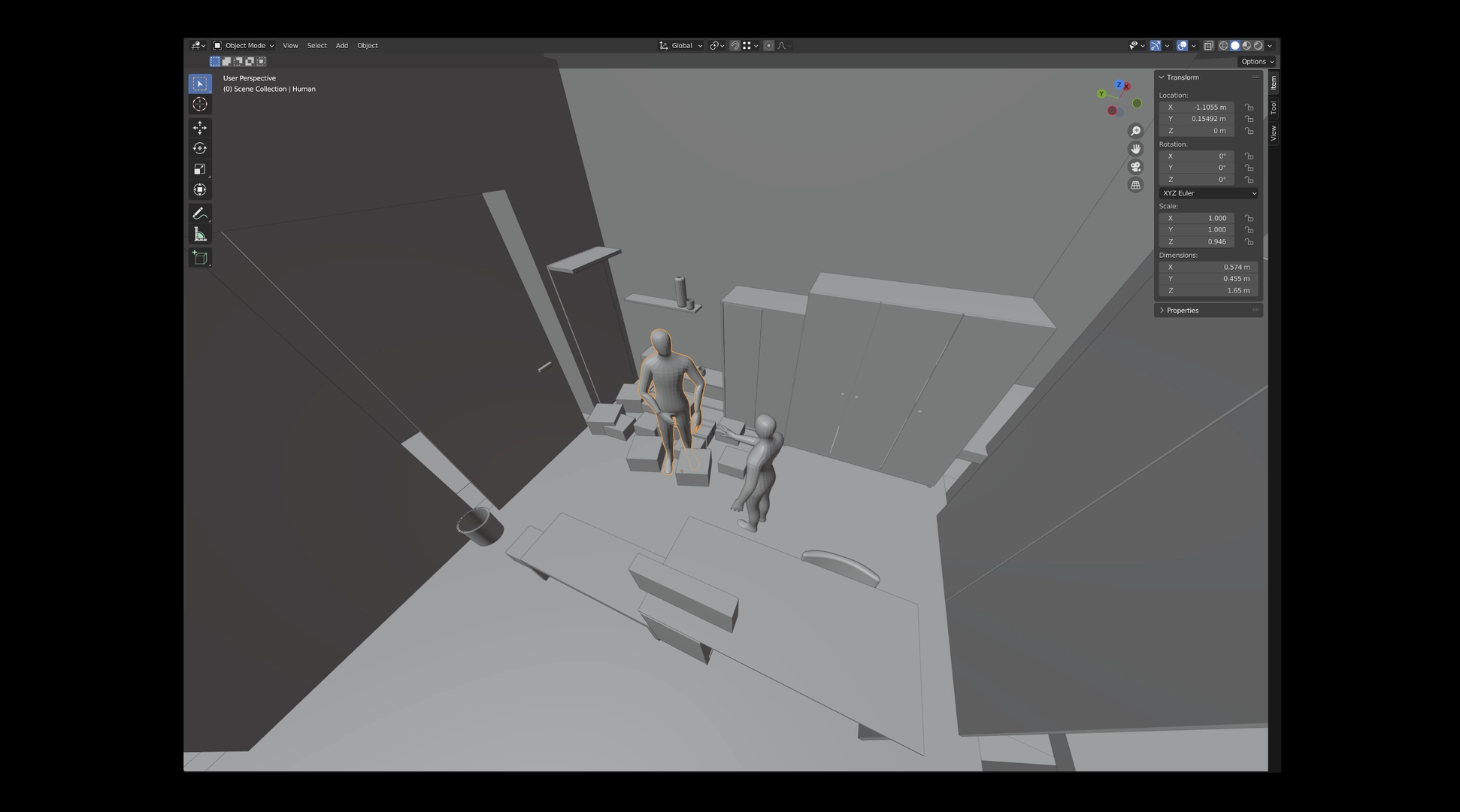

The moment of the explosion

I heard a popping sound, and in a split second, I saw a metal door flying at my wife and me. Then I was thrown back, and my wife was covered in shrapnel somewhere near me. At first, I didn’t realize what had happened. Only in 2-3 seconds I discovered that there had been an explosion.

Everything from the ceiling fell on us, almost all the construction debris. And I screamed, “Zhenia, are you alive?” There was a feeling of numbness: you don’t understand anything; you don’t think about anything. I looked at my wife: she had one earring in her ear — the shock wave had blown off the other two. I don’t know how it’s possible, what kind of explosion it was, I can’t imagine. It felt like the air shrank and expanded after the pop. We had bags of cat food, which just ripped to pieces from the inside because of the explosion.

After that, I had a whole-body concussion because the impact was quite powerful. I had bruises under my eyes afterward. I noticed that my shoulder muscle was broken into two parts. I don’t remember what happened next very well.

The place where Serhii and Yevheniia were at the moment of explosion of an air bomb. ©Center for Spatial Technologies