Yevheniia Zabohonska

Yevheniia Zabohonska was born and lived in Mariupol. She has worked at the Mariupol Drama Theatre since 2002, first as a lighting technician and later trained as a lighting director. Her husband, Serhii Zabohonskyi, also employed at the theater, contributes his perspective as one of the witnesses in our research.

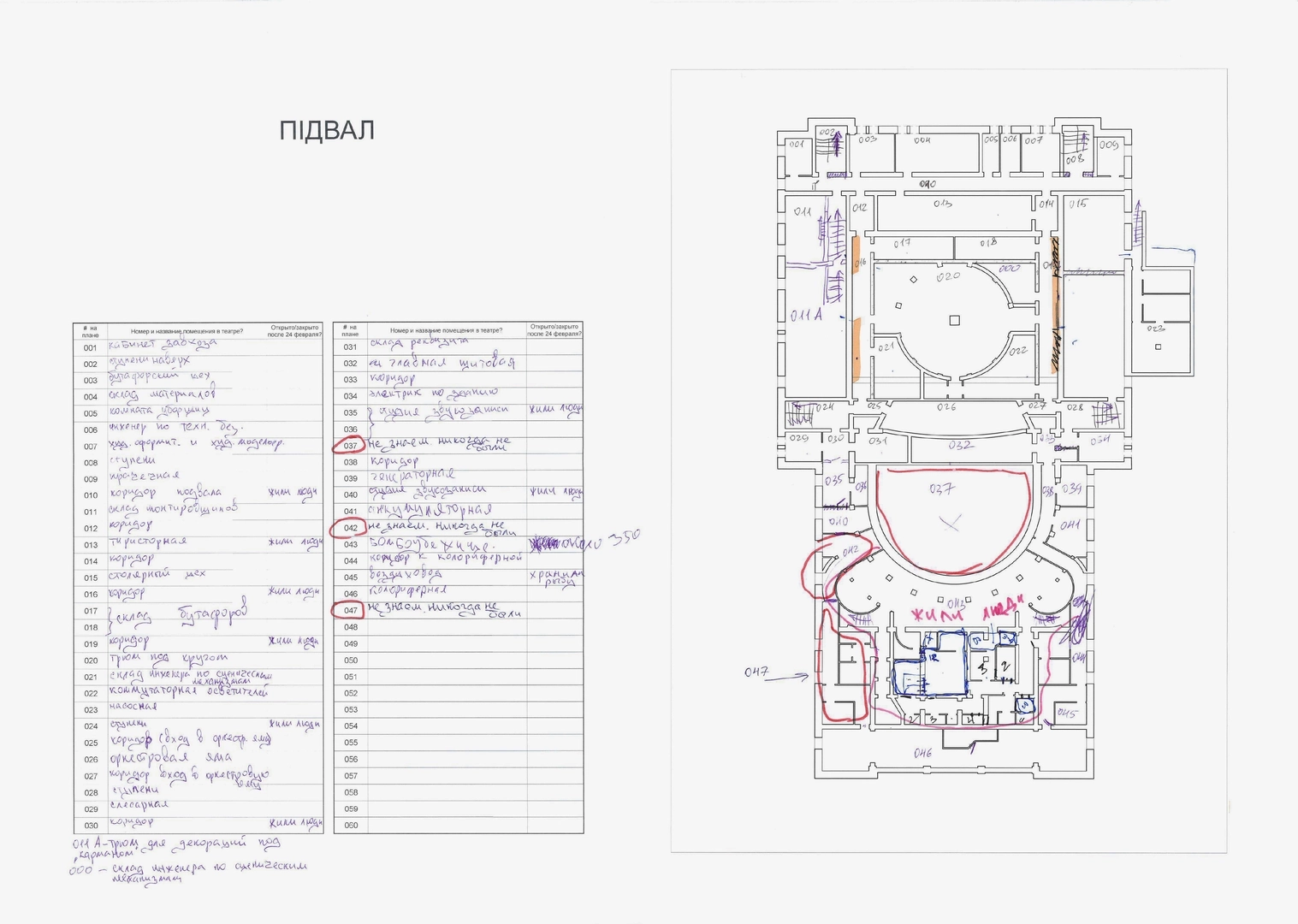

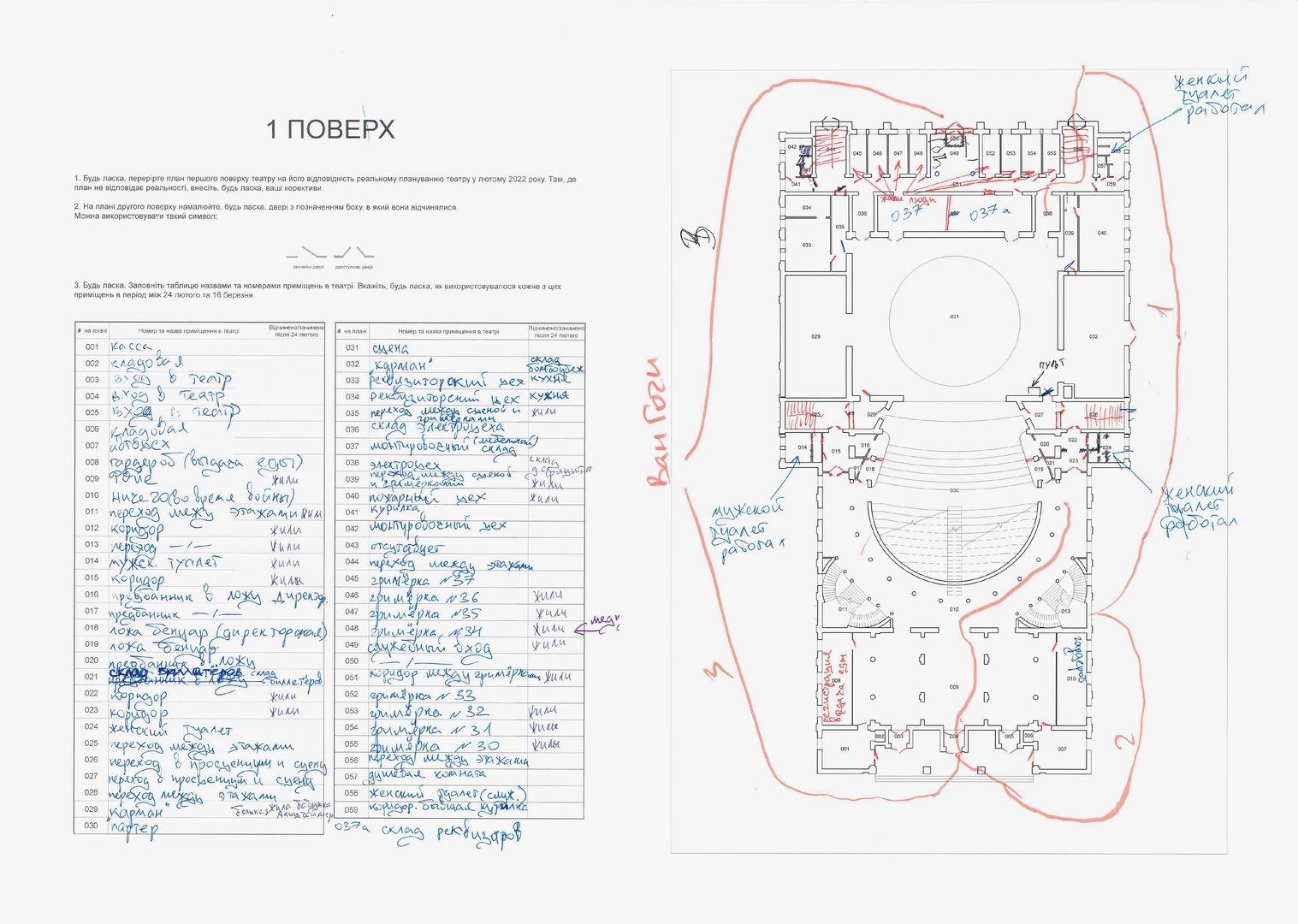

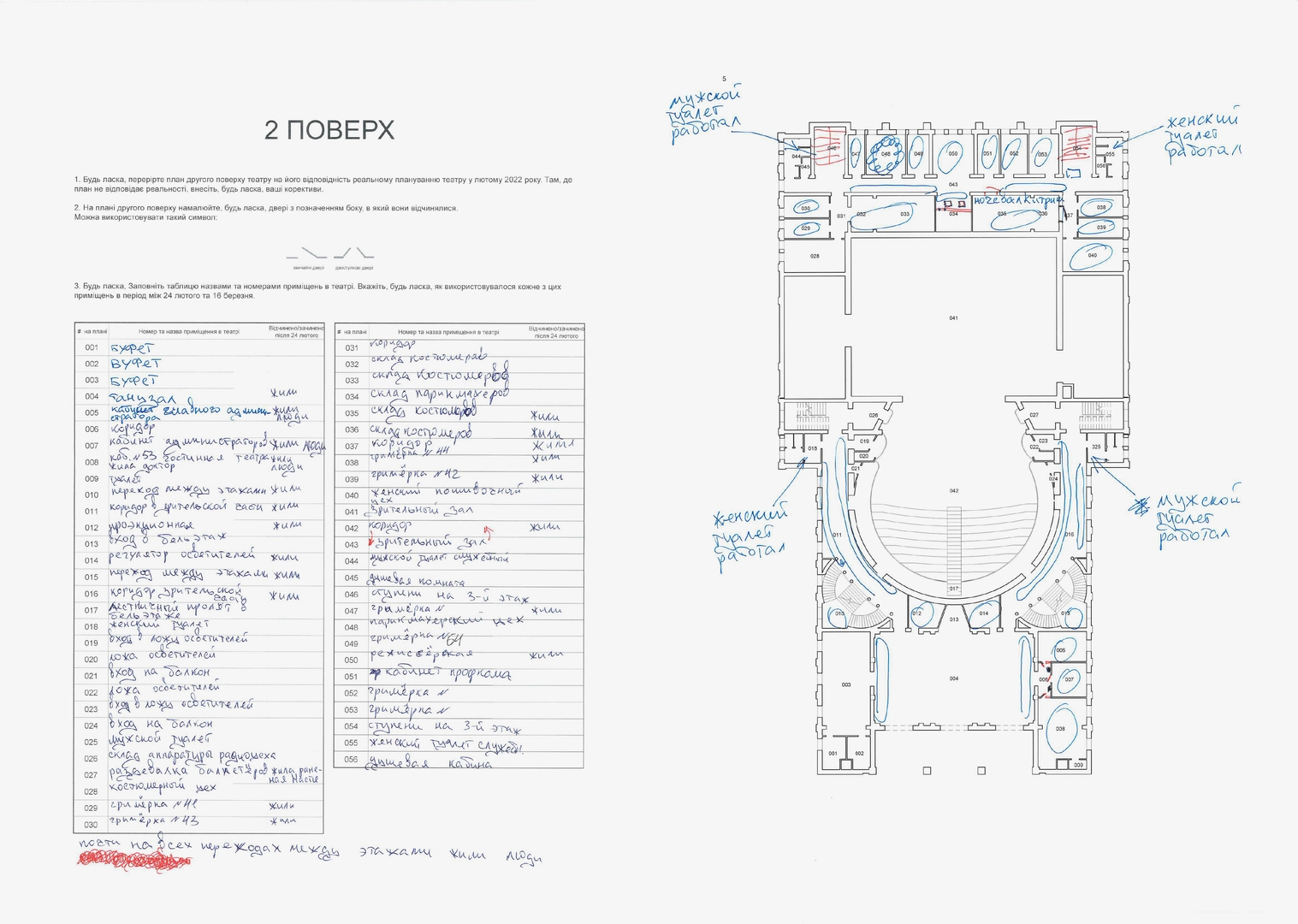

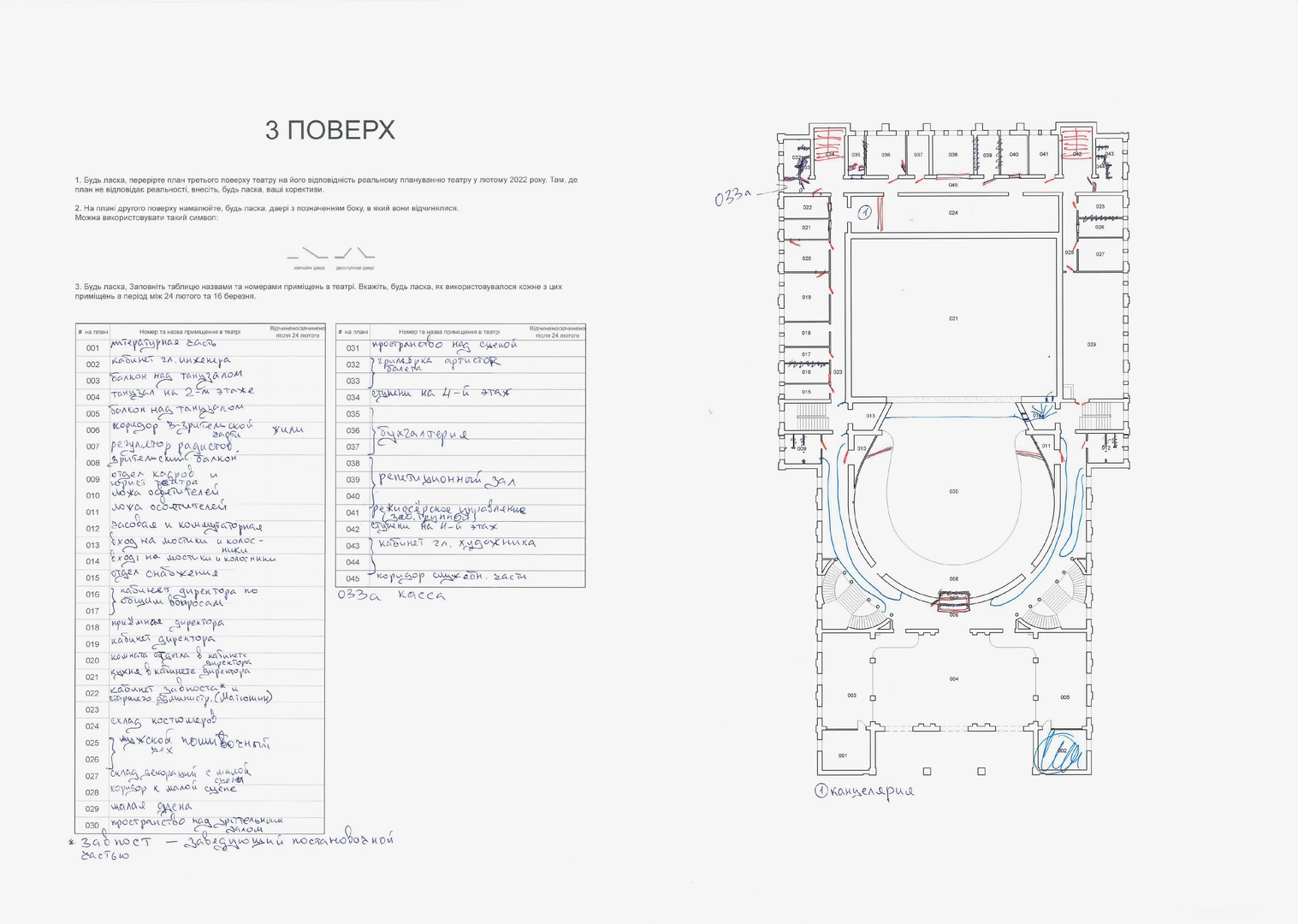

Following the war's escalation, Yevheniia, lacking a bomb shelter at her home amidst intense shelling, sought refuge with her daughter at the Drama Theatre on February 24, 2022. But as more and more people began to arrive there in early March, Yevheniia took on the role of volunteer coordinator at the theater, where she and her husband helped to reorganize the space to meet the needs of up to 2,000 people.

On 16 March 2022, when the Russian Federation army attacked the Drama Theatre, Yevheniia and her husband were almost at the very epicenter of the explosion – in the electrical workshop on the theater’s stage. Trapped under the rubble, they managed to get out and eventually left Mariupol.

In an in-depth interview, Yevheniia told us how the theater space was transformed into a shelter, described the forming and work of the theater’s volunteer group, outlined the difficulties faced by the theater’s residents, and depicted the aftermath of the explosion at its epicenter in the first moments following the attack.

These are selected fragments of an in-depth interview with Yevheniia, supplemented by visualizations, photos, and plans that describe the transformation of the theater’s spaces.

The beginning of a full-scale invasion

Mariupol woke up on February 24, 2022, to horrible explosions. The whole city was shaking from the very morning, and in the evening, it only intensified. We had no basement in our house, no bomb shelter, nothing. So I texted the theater director that I would go there with my youngest daughter, thinking it would be safer. My husband and son stayed home. I was the only one in the theater on February 24.

A few people began to come to the theater after the list of bomb shelters in Mariupol appeared on the website of the city administration on February 25, 2022. The Drama Theater was listed there, too1.

Initially, individuals sought refuge in the theater to escape the bombings, planning to return home once the shelling ceased. The general assumption was that the situation wouldn't escalate.

More and more people were learning about the shelter, but volunteer organizations still did not know about us. It was only through a police update during a meeting that the city government learned about the significant number of people taking shelter and the urgent need for food, medicine, water, and other supplies.

But when the evacuation from the city was announced — I don’t remember exactly what date it was, I can’t say for sure. Actually, we didn’t care about it at all — that day, we were horrified by what happened after the announcement2. People started to come to the theater, but the police announced that the evacuation was canceled, and this mass of people who could not return home again rushed to the theater. People were very irritated, very frightened, and the crowd was absolutely uncontrollable. They rushed into the theater and began to settle, some here, some there. Immediately, they started looking for chairs, armchairs, and they started breaking down the auditorium to find somewhere to sit and lie down.

Residents’ attempts to evacuate from Mariupol

Every day, a crowd gathered outside the theater, hoping to evacuate. People were clinging the white cloth on themselves, wrote “Дети” (“Children”) on their cars and tried to get through. I don’t know where the information about the evacuation appeared, but people somehow found out about it.

Misha, our cook, and I were watching from the foyer how many people had arrived and said, “How many more people do you think we’ll have today? Well, it’s okay. We’ll put in one more boiling bowl to have enough food for everyone.” Every day, we had a flood of people: there were more and more and more and more. We were promised that there would already be evacuation buses that day, but there was not a single evacuation.

Appointment of Yevheniia as coordinator of the theater’s volunteer group

The police came one day and asked the residents, “Who is the person in charge here?” And everyone answered that it was me, although I didn’t volunteer. I was just helping people because I knew more than others. And that was it. The police came and said that I was the “caretaker” of the theater. I was appointed without notice.

Why did I do it? Our watch was on duty for twenty-four hours and went home, and I was there all the time. In addition, I worked in the theater for a long time, so I knew both the building itself and communications. My work was directly related to that. That’s why I helped people to settle in, organized places for them, laid wooden planks for them, took off the curtains, and laid them as mattresses. While there was gas, my husband and I would run back home — we lived nearby — and boil water and bring it to the theater. My husband would look for food, cook something, and bring it to the theater, too, so that people could eat, and so could we. That’s how we survived the first few days.

Daily life in the theater

As new people arrived, we organized everything that was necessary to welcome them. I cleaned the toilets, and Serhii did “public relations.”3 Other guys organized the kitchen and worked there. There were more and more people in the theater, and we just did not have time to do everything. People started coming up and asking how they could help. After that, we organized a lot of different “services”: for example, a security service that boarded up windows and procured technical water and firewood, as well as services that monitored the processes. There were women who helped me keep the toilet facilities clean. And there was a couple who set fire to the garbage. Because of the large number of people, there was a lot of different garbage, and in order not to get overwhelmed by it, we took out a huge 200-liter metal barrel from the performance “Maidan Inferno,” and then we began to burn garbage near the theater.

Each service had a person in charge, and we would meet at eight in the morning for a meeting, where we would discuss which service had problems, and if there were no problems, the person in charge would leave. And there stayed only those who had some problems and needed to find a solution. Somehow, we self-organized quite quickly, to be honest; I was shocked at how it all happened.

Every day, I got up at six in the morning and went around the theater to see how people had spent the night, talked to the guards, and asked how the night went. And then I’d go outside and see if the guys in charge of the fires had started making them.

We lived like a commune. Everyone supported each other; there were never any scandals nor fights. Even in the queues for food, it was calm. Just imagine what a crowd of people it was. Of course, there were disgruntled people, too. Someone complained that they were not given enough food, but we replied that they were not the only ones there and it was necessary to divide it somehow because we did not know how long we would have stayed there and how much food we would have had.

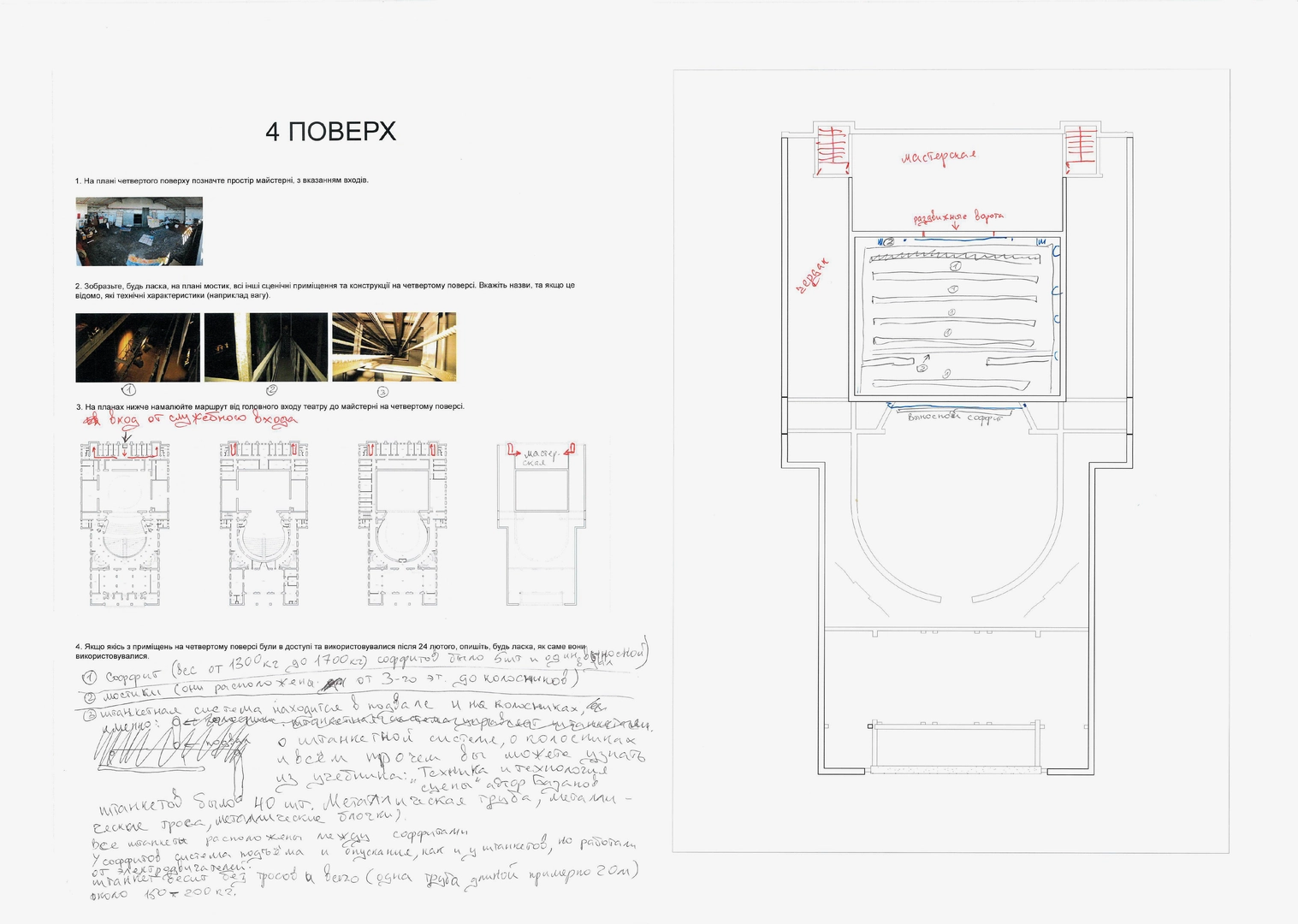

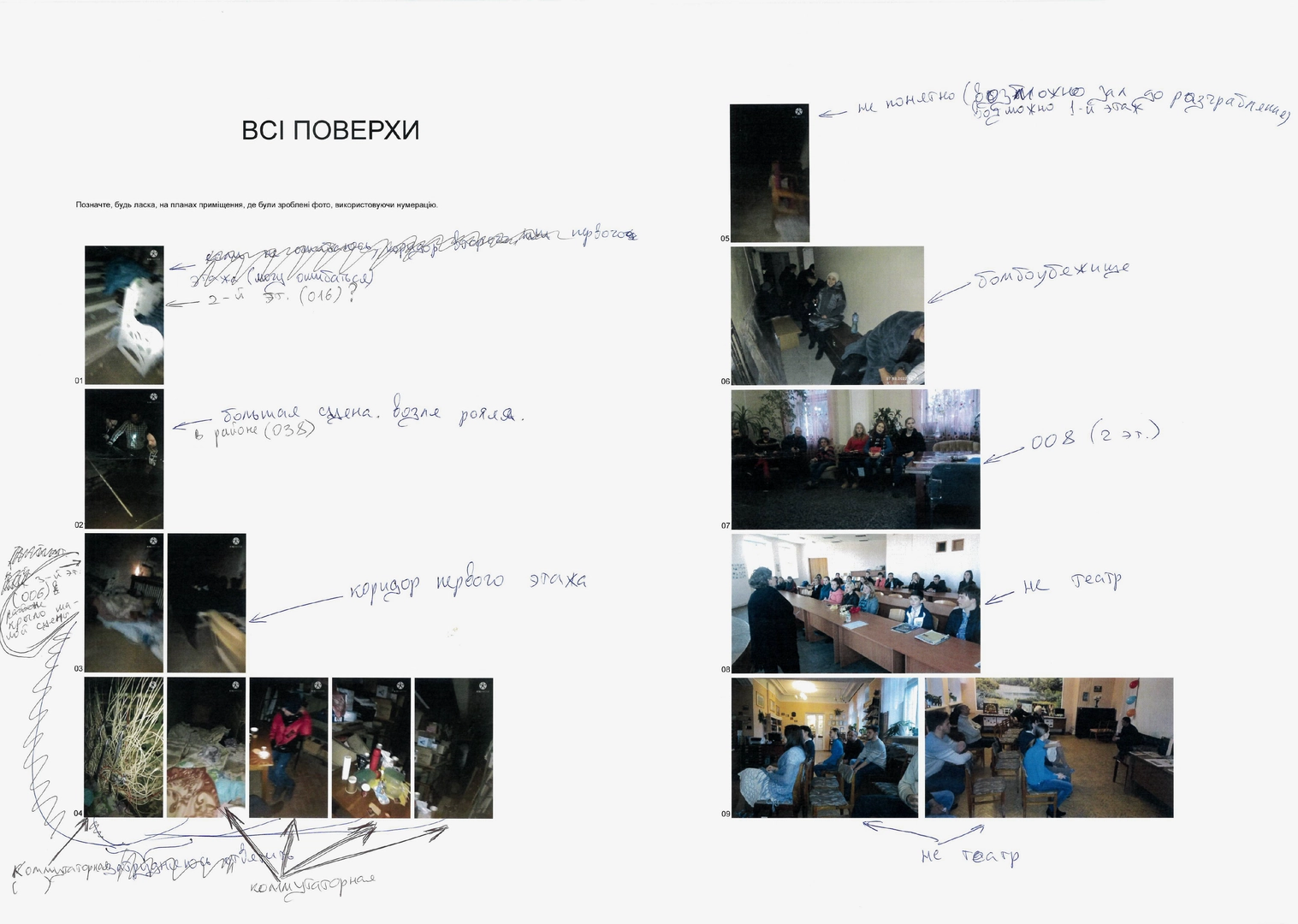

Theater as a shelter: reorganization of theater spaces

Anyway, the hall was trashed in a matter of days. It was very sad; it was madly painful to look at, because it was all dear to me. I know how our directorate achieved everything, what paperwork it was, all those repairs and purchases. Then, I gathered the men who lacked something. I told them to come with me, and we pulled everything they could from the furniture workshop. There were different beds, chairs, sofas, everything that was used in the performances, as decoration, on which you could lie down, sit down. Everything I could, I gave it all away. My daughter and I slept in the basement, there was a wooden shield, and some cloth was laid on top, and my daughter and I covered ourselves with the cloth.

Then we realized that we had to feed people somehow. Many people came and thought we were all volunteers, but it turned out that we were not volunteers at all, and nobody in the volunteer groups knew about us until my husband ran and told everyone about us. And after that, humanitarian aid, water, food, and medicines started to be brought to us. The police brought food and medicine. Volunteer organizations brought household items, pastes, towels, clothes, some socks, and children's tights. In general, they brought whatever they had.

We converted the checkroom into a kitchen. There were two windows, one for serving and the other for the census of people in the building. The girls who did the census sat in from ten o’clock in the morning. There was a logbook for each neighborhood in the city, and the girls alphabetized the people who came to us. The police told us in what form to write it all down: we wrote down surname, first name, patronymic, year of birth, actual address of residence in Mariupol, and phone number. I am 100% sure that these journals were intact because there was no fire in this part of the theater; the foyer and closets were intact. I’ve watched different interviews already with people walking through the lobby. And these log books were still there, on the window in the enumeration room. People were finding each other through these log books, which was very pleasing, of course.

How was the food provided?

There were a lot of people, and we started cooking together on the fires, first with what people and police brought us. But there were more and more people, so we couldn't boil that much. We didn’t even have the big pots we needed to boil for so many people. We talked to the police, they asked what we lacked, and we said a field kitchen was needed. Two hours passed, and we had the field kitchen. How happy our cook Misha was, I can’t tell you, I still remember that. He was glowing, and he immediately distributed everything: Today, we cook this; tomorrow, we cook that. He was so happy.

Over the next weeks, the police brought us food, and we tried to cook the most perishable items immediately. For deeper-frozen foods, we found a deep room in the basement and used it as a refrigerator. The owner of the One Gogi Cafe next to the theater also allowed us to take two freezers, like ones for ice cream. The police also brought us a generator, and we turned it on periodically to freeze the freezers and let people charge their phones at the same time.

The scarcest items were wet wipes and infant food. The police also brought us bottled water, which I kept in my warehouse and gave out only for babies so they wouldn’t get sick. I poured this bottled water and poured baby food according to age separately into disposable cups. I kept it all at my place, and I was the one who gave it out.

Communication between people inside the theater

Our phones were on their last leg. Some of us had no phones at all. To make decisions or contact each other, we could only get together and just talk. If someone needed something, they found me, my husband, our colleague Damir Sukhov, or other volunteers. If someone could not solve the problem, they would look for me, and I would help them find a solution. It worked like word of mouth.

Medical care in the theater

It was already -10°C outside, cold, with no heating, no water, no basic necessities, and people arrived naturally already sick. We organized a first-aid post in the theater, but of course, medicines were in short supply. People constantly came to our doctor with very high fever or intestinal disorders because they drank unboiled water. There was not enough food, so we had to eat spoiled food. Because of this, we needed medicines against intestinal viruses and antipyretics for children and adults. We also had a shortage of sedatives and antidepressants because so many people in the theater were having panic attacks. In addition, there were people in the theater with diabetes who needed insulin. We wrote lists of medications and gave them to the police, and they tried to get whatever they could.

Shelling on March 15 and 16, 2022

On the night of March 15 and early in the morning of March 16, there was a terrible bombing of the city. The shells were flying endlessly, the ground was shaking. And this was the first time I had been scared in three weeks. Whatever had happened before, a mine exploded somewhere, something fell somewhere—I didn’t pay any attention to it at all; everything was fine. But on that night, I was insanely scared. I was awake and walking around the theater. The people in the theater were not sleeping at all—they were sitting by candlelight and praying. The guards were awake; nobody in the theater was sleeping. And there were such blast waves that, when I went around the theater again at 6 a.m., I saw our huge six or seven-meter stained glass windows on the second floor in the parquet hall, hanging in the air. That is, they were so damaged by the blast wave that they could have fallen inside the theater onto people walking or sitting there.

It was scary, as well, when they bombed Central Market4. My house was right next to it, and I remember how I came out of the theater at 6 a.m., looking and thinking, “What's that smoke? Is it my house or not? Should I run and take a look?” And then the guys came and said it was the Central Market on fire.

On March 15 and early in the morning of March 16, 2022, some of the theater’s residents left the building through the de facto evacuation corridor agreed upon by the Russian side. Yevheniia describes the day of the attack on March 16, 2022:

At 7 a.m., as dawn broke, it just felt like the theater had been hollowed out. So empty was it that I hadn’t seen it like that in those three weeks. We walked around the theater and looked at the number of seats that had been vacated and realized we needed to clean up a bit and prepare seats for, shall we say, incoming people.

All our life went on as usual: bread was kneaded from the evening, fires, sanitary facilities, putting things in order, updating meetings. Serhii and I tried to find more places for settling people; we took the key to the room near the small stage on the third floor and were going to go there to see if there was space.

The thing is that Serhii and I could not walk around the theater without anyone constantly asking us to help do something, to solve some issues, to give something. So I said to him, “Let’s go to the workshop and talk there.” We went to the electric workshop at the back of the stage. It was a small space and consisted mainly of load-bearing walls and fire-proof doors. We went in there and started talking, and it was literally a minute and a half or two minutes until the explosion happened.

At first, there was a terrible ringing in my left ear, then I saw darkness with sparks in it. I remember – darkness, then sparks, and I feel like I am laid on a pile of something. And then I start to fall asleep. I realized that something had happened. Then, when everything became quiet, Serhii shouted, “Are you alive?” I yell that I’m alive. He was the first to get out from under the rubble and started taking out my rubble. I had a burned left side of my face, a contusion of my left ear, fractured and cracked ribs, and shrapnel in my left leg. I looked around and was horrified. In just a few seconds everything around us had turned into a mass of splinters, fragments, heaps of rubbish. In an instant, nothing remained intact.

It was impossible to go backstage. There, for one thing, was a haze of plaster, and something seemed like a tangle of metal equipment from the auditorium. All the cables, pipes, and metal from the footlights, which were about five pieces of several tons each, all tangled, as in horror movies. Secondly, the hall and the stage before the blow were separated by a fire curtain made of asbestos. And at the moment of explosion this asbestos scattered in different directions. It was such an impenetrable haze.