A City Within a Building

Author:Ksenia Rybak

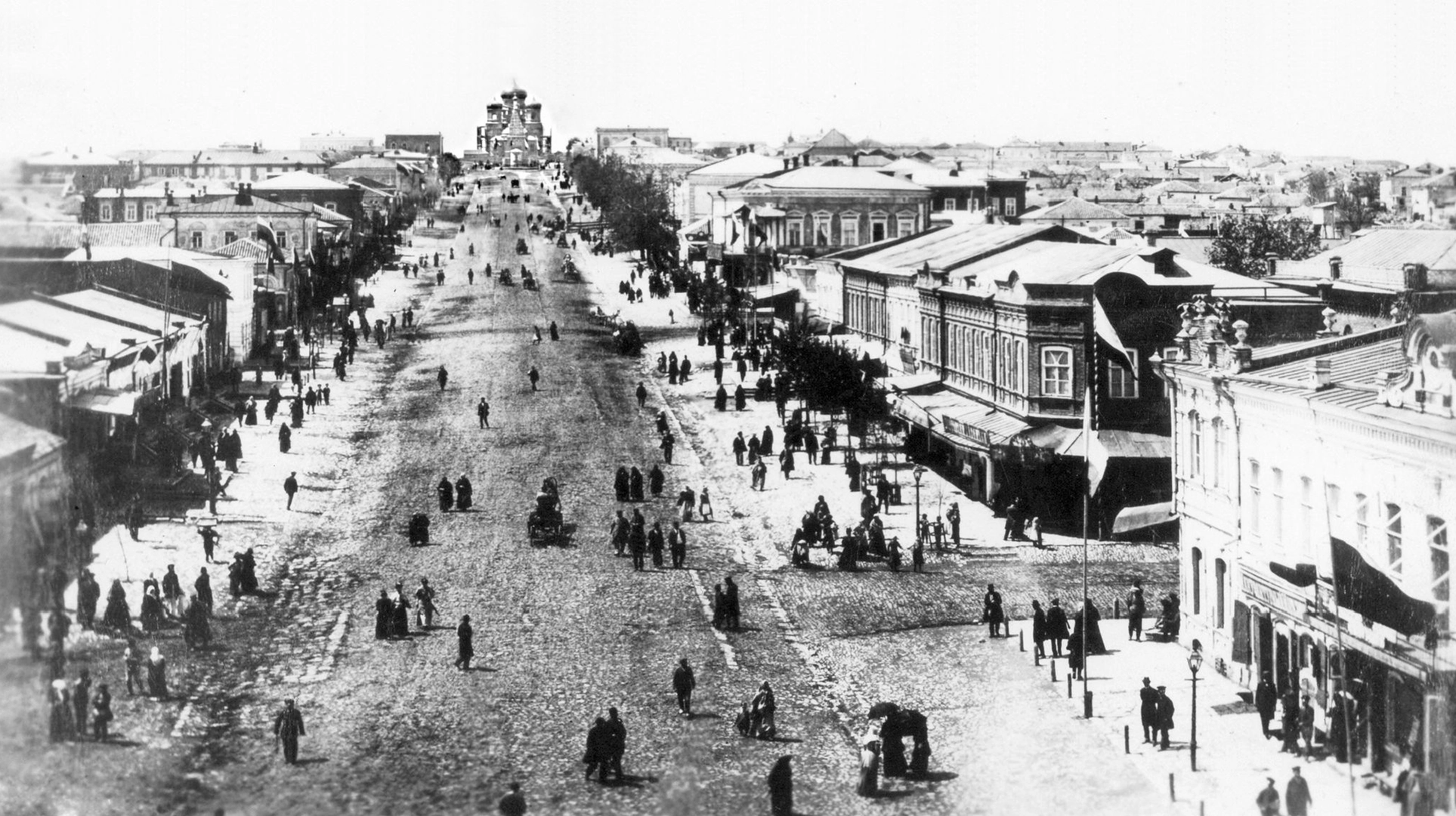

When Russia’s war against Ukraine escalated on 24 February 2022, the city of Mariupol was one of the first places targeted in a three-month siege that left 95% of the buildings either damaged or destroyed and tens of thousands of people dead2. On 25 February 2022, the last evacuation train was able to leave the city1. Since then, Mariupol has been under siege until the city’s total occupation by the Russian forces. During the blockade, dozens of large and hundreds of smaller bomb shelters emerged here. Among the largest of them was the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater in the very heart of the city — the locals called it the Drama Theater. During the blockade, it gave shelter to at least 2,000 people who sought refuge there up until the Russian attack on the theater on 16 March 2022.

While working with this war crime and studying processes that emerged in the Drama Theater during the blockade of Mariupol, we realized that this place of tragedy had also become a space of consolidation and mutual aid. For two weeks after the beginning of the escalation of the war, residents of Mariupol were forced to live there without heating, access to drinking water, or means of communication3. But this involuntary cohabitation turned into something more than a way to survive. The Drama Theater was transformed by the tactics of resistance and defense employed by the people seeking shelter within its walls. In the process of production of the space around them, these people’s practices of self-organization and mutual aid made a material imprint in the theater space.

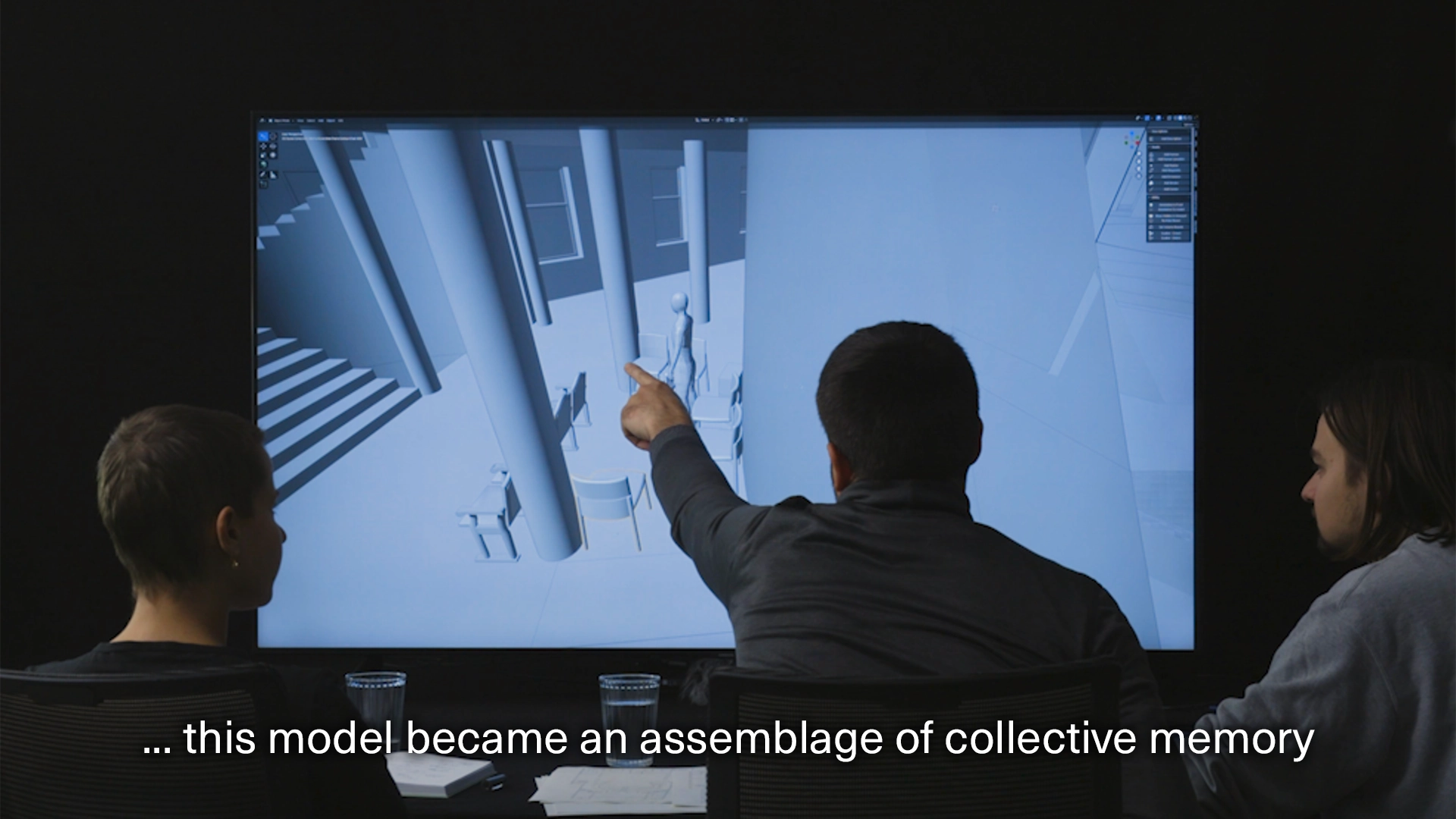

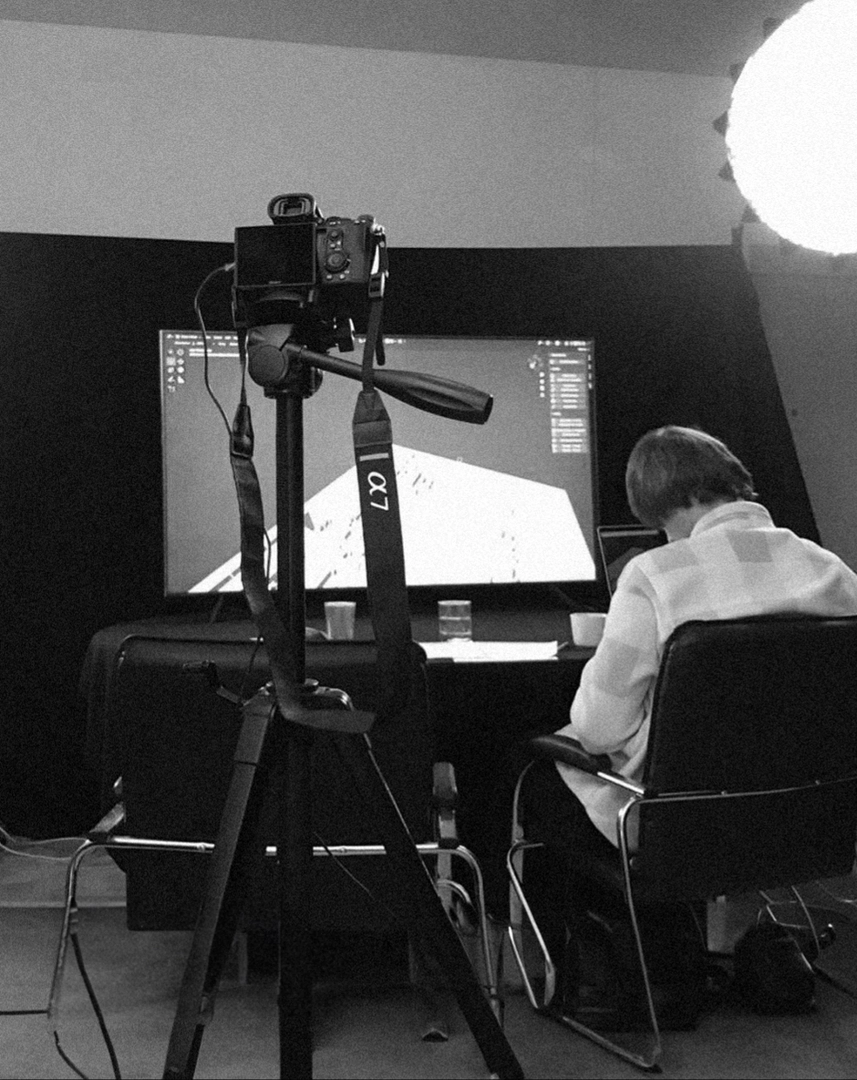

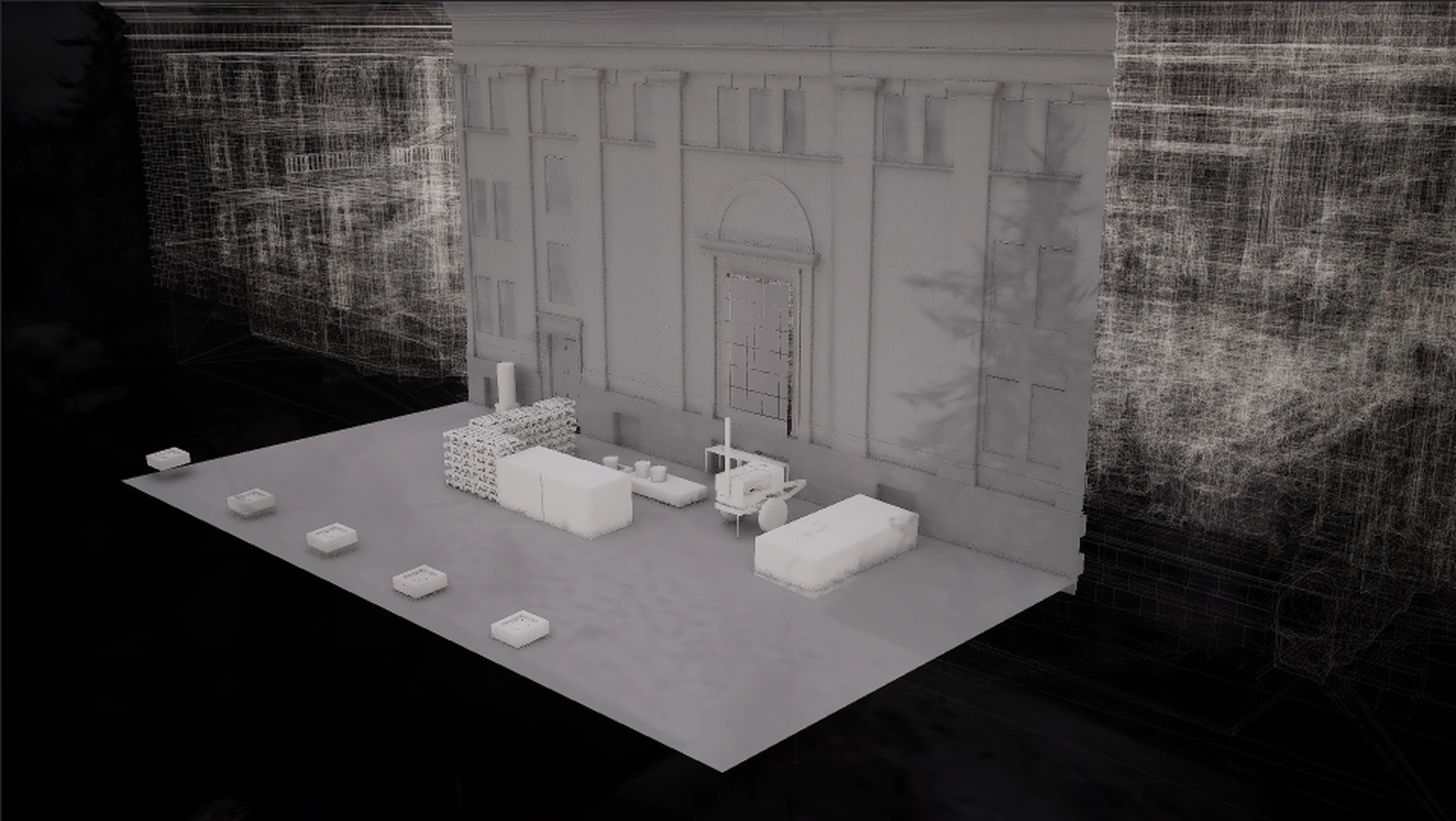

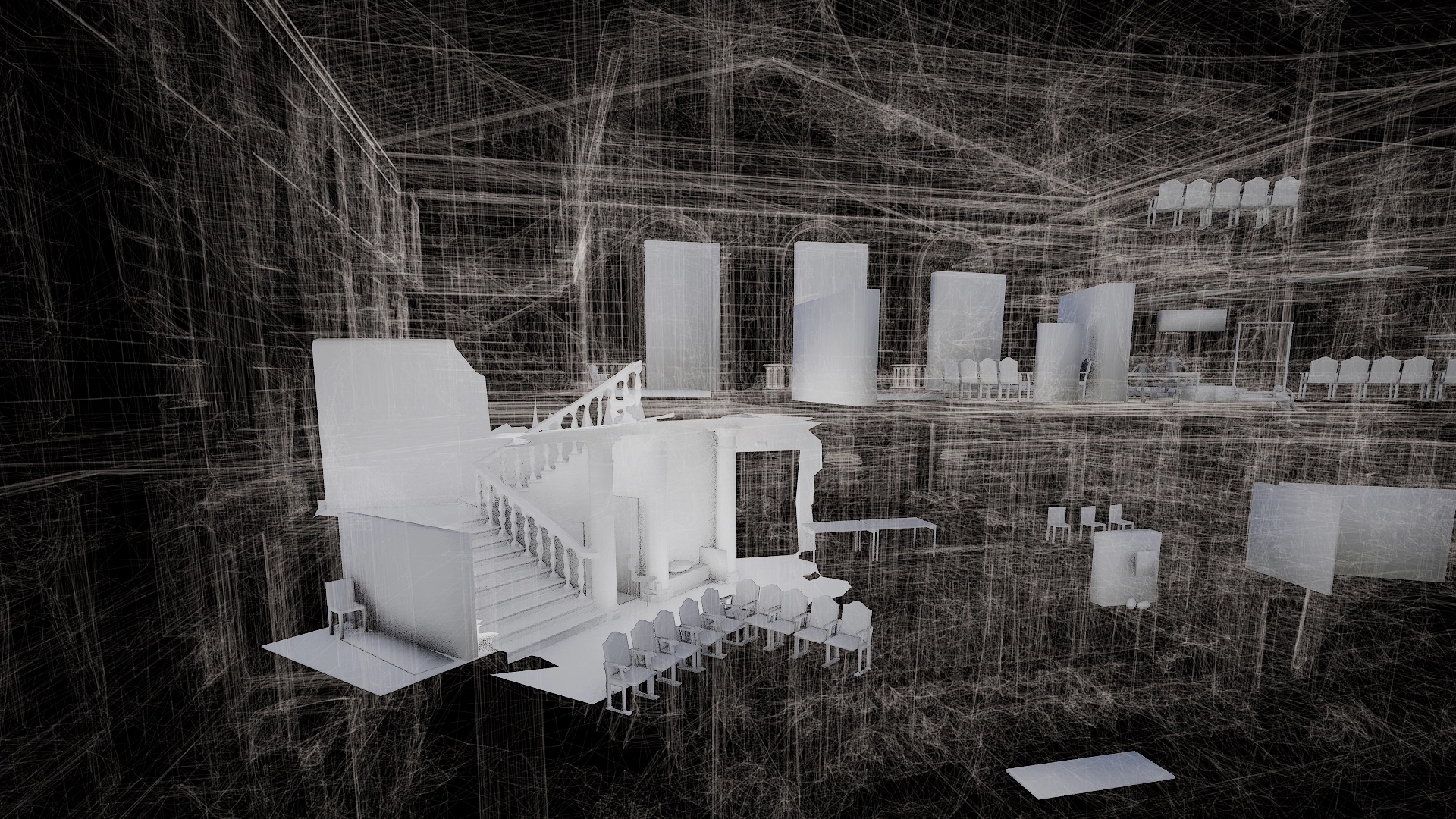

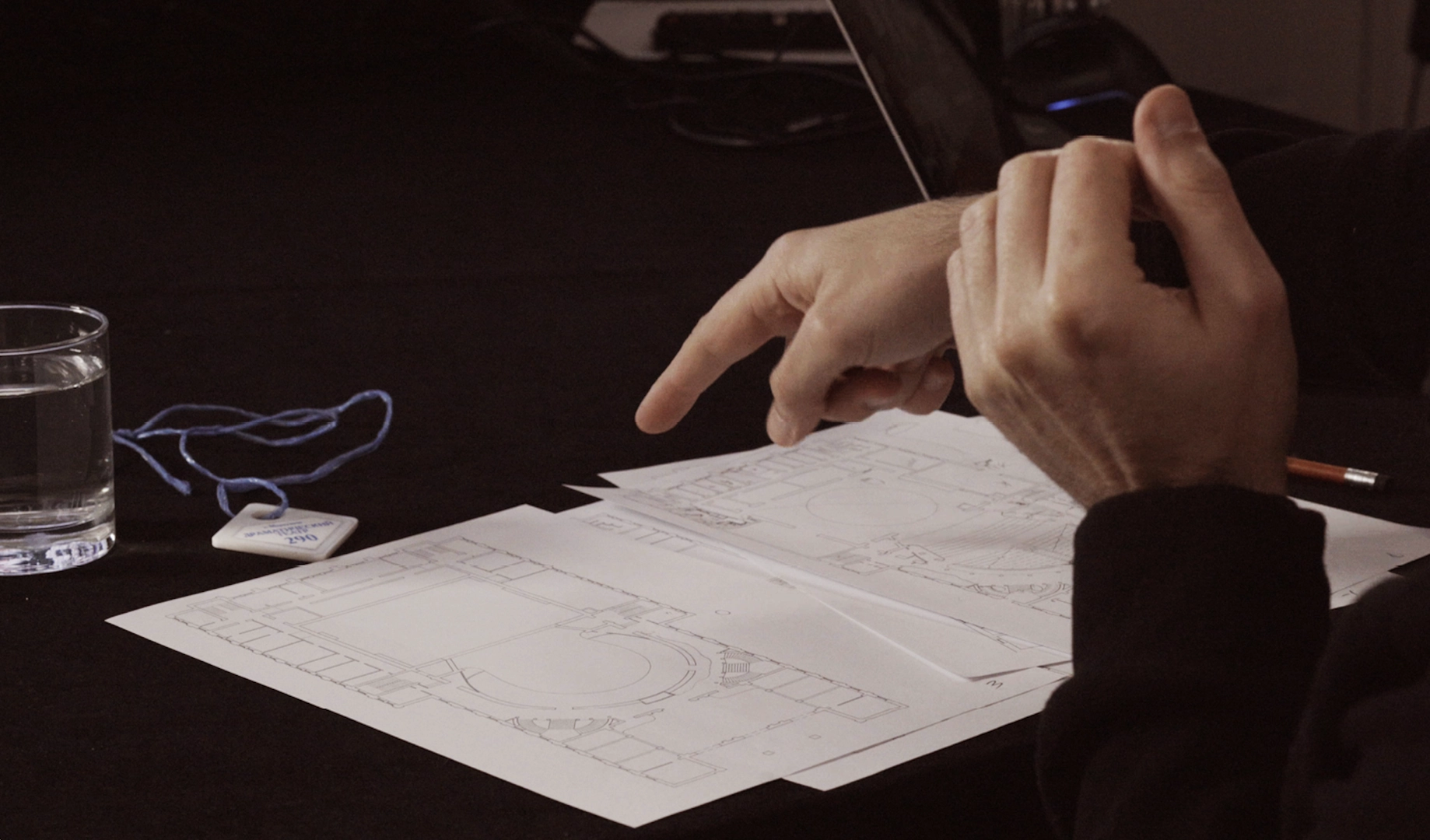

Based on images, videos, and the testimonies of 27 witnesses4, we attempted to understand and recreate the architectural transformations within the theater, with particular attention to the newly ascribed functions of various elements in its space, as well as the organization of life in the theater. This allowed us to see what was destroyed by the air strike: the social fabric that emerged here was not that of a homogenous crowd, but rather a special social space produced by various groups of people and their practices — a city within a building.

The theater as a shelter

How the theater became one of the city’s central shelters

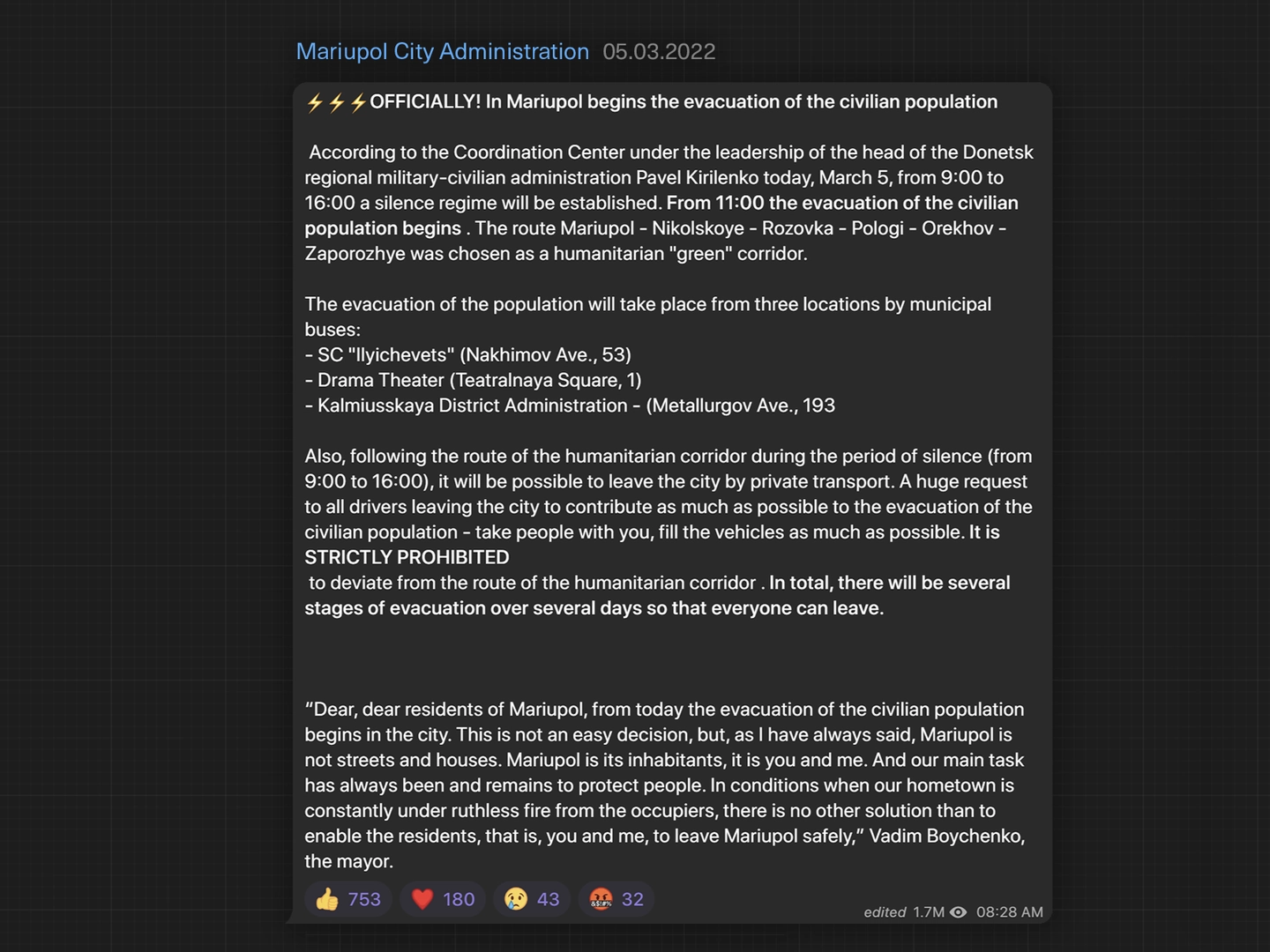

On February 25, 2022, the Mariupol City Council designated the Drama Theater as an additional shelter with limited functionality, operating only during air raid alerts. Therefore, while individuals sought refuge in the theater overnight, it was primarily on the initiative of its staff, as neither the city administration nor the police were aware of its status.

However, the situation shifted, with the announcement of the first evacuation corridor agreed upon with the Russian side on March 5, 2022. Three key evacuation centers were announced, one of which was the Drama Theater. Hundreds of people came there from dozens of different districts in the hopes of eventually leaving the city or, at least, finding some temporary refuge from the incessant shelling. Yet, while awaiting evacuation buses, the police reported a breach of the ceasefire by the Russian army. Mariupol residents hoped that the evacuation from the Drama Theater would still be carried out in the following days. During that time, bombings in the city were intensifying, and many residential neighborhoods had already been destroyed, so most of the people who flocked to the theater with the intention of evacuating ended up staying.

A witness of the 16 March attack, Mariupol resident and actor Dmytro Murantsev, who came to the theater in order to evacuate, shared his first impression upon his arrival to the theater with us: “It was just in such high contrast [with how the theater looked like before the escalation of the war] the feeling I got when I entered the Drama Theater [...], on the 5th of March. [...] its aristocratic interior, none of it could be seen anymore. It felt like it was entirely made of people. You couldn’t see the walls, couldn’t see the columns.”

Day after day, the police informed the people that the Russians were not approving the evacuation of civilians. At that time, people of various ages, families with children and pets5, people with disabilities, vulnerable population groups, and residents of Mariupol and its suburbs were still converging towards the theater. “Many just came with their luggage during the day,” notes Oksana Mazina, a witness of the attack and a Mariupol resident. “They waited for that corridor and then left to spend the night at home. And the next morning they came again, they waited.”

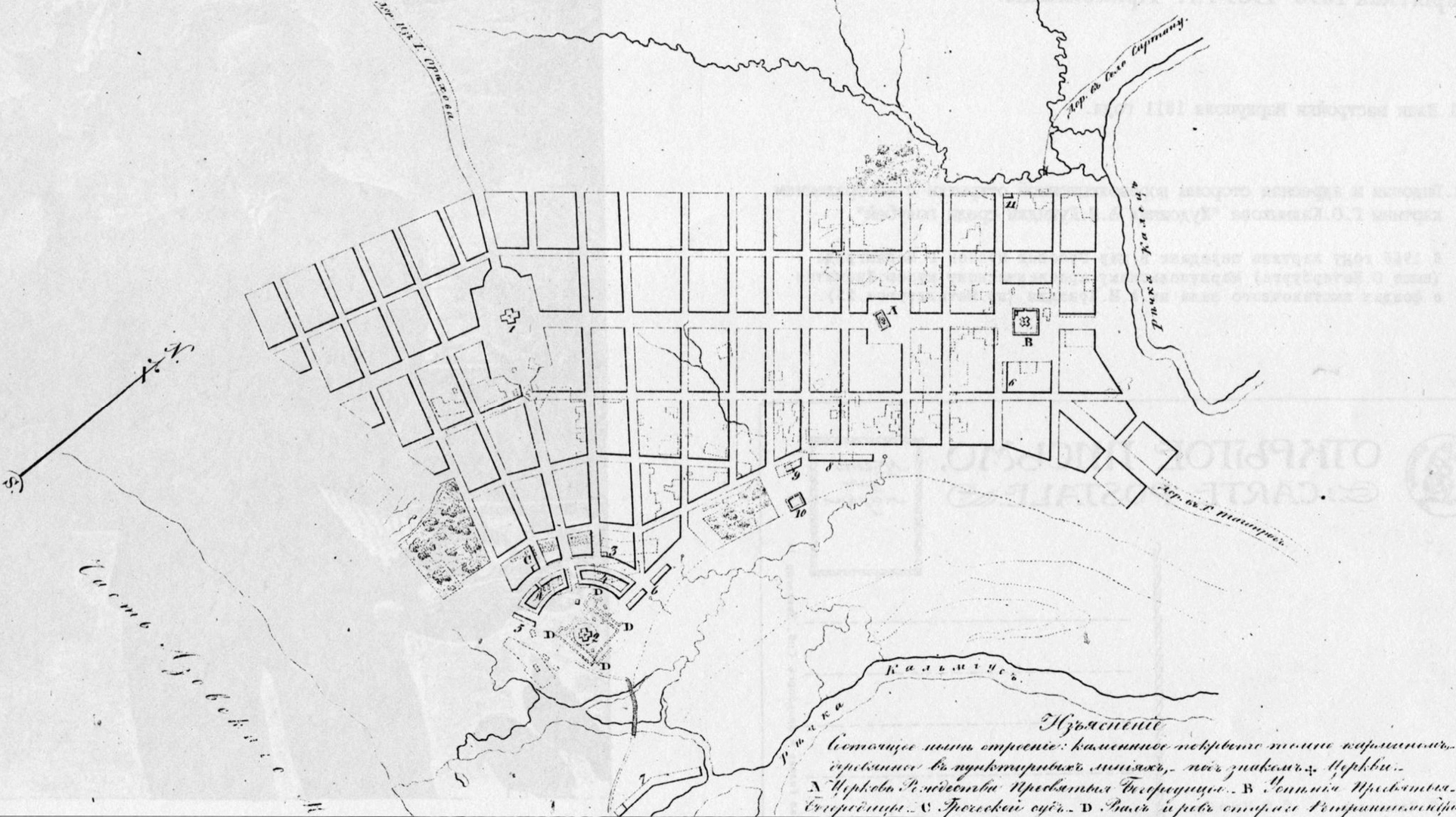

The Drama Theater evoked special trust as a shelter, and there were reasons for this beyond its status as a key evacuation center. First, it was located in the central part of the city, which was less subject to bombing during the first days of the war. In addition, it felt safer because it was separated from other buildings by the city’s central square. It was located far away from any potentially legitimate military target. Crucial, too, was the theater’s status in people’s memories, as most witnesses in this study said that they had personal associations with this cultural institution and felt safer here because of that.

The area of destruction spread across the city as strikes from military aircraft and artillery intensified near the encirclement line. Residential areas, along with crucial infrastructure such as medical facilities, energy plants, transportation hubs, schools, and museums, were destroyed. The systematic implementation of the tactic of urbicide6 by the Russian army transformed the theater and similar large shelters into support centers for Mariupol’s volunteer groups and police.

More and more people were arriving at the building because municipal services often directed them there. Oksana Mazina confirms that, as the bombings intensified, the State Emergency Service of Ukraine directed people from the destroyed houses to the theater. On top of that, when the Maternity Hospital No. 3 was bombed on 9 March 20227, municipal services and the police brought pregnant people, people with newborns, and their relatives to the theater8. Two anonymous witnesses who participated in our study were among these people.

The number of people in the theater quickly exceeded the number that its dedicated bomb shelter9 or at least the basement rooms could fit. For this reason, people began to settle on the first, second, and third floors, which did not offer the same degree of protection as the underground spaces—the building could no longer guarantee safety to the high numbers of people who continued to arrive. As a result, the community undertook the functions of protection which was originally built into the architecture of the theater.

Self-organization in the theater

The presence of over 2,000 people prompted the emergence of self-organized communities to fill in the gap left by the collapse of the city administration. Theater employees, along with other residents formed a volunteer group of oscillating between 40 and 70 members. This volunteer group had a coordinator—the Drama Theater’s lighting director, Yevheniia Zabohonska. Yevheniia recalls: “One day, the police came and asked the residents, ‘Who’s in charge here?’ And everyone said that I was. Even though I never claimed to be, I was helping people ‘cause I knew more than others. That’s it. [...] I was appointed regardless of my opinion.” Despite Yevheniia’s spontaneous appointment as the “accidental” coordinator, the decision was not random. It was based on her deep understanding of the theater’s layout, its service rooms, and communications.

Ihor Navka, a Mariupol resident who worked at the Illich Steel and Iron Works, recalls that his wife Nadia Navka spontaneously began helping out in the Drama Theater’s kitchen: “In a day or two [after they came to the theater], she saw Zhenia [Zabohonska], who was organizing us all [...] she comes up to her, stands there and says, “I wanna help.” She [Zhenia] says, “Great, let’s go.” [...] she asked her, “What can you do? What are your skills?” She says, “Let me do the cooking. I’m a cook. I got vocational training.” She goes, “Awesome!” and takes [Nadia] to the kitchen.”

The volunteers oversaw all essential aspects of daily life in the theater: they allocated living space, cooked meals, provided first aid to the wounded and treated the sick, distributed basic necessities, and ensured that the power generators worked. Key to the functioning of this burgeoning shelter was the creation of the field kitchen and the medical station, assembled by these volunteers first using whatever makeshift supplies they had to hand and later supplemented by equipment received from the military and police.

How the theater space changed

Accommodating the people

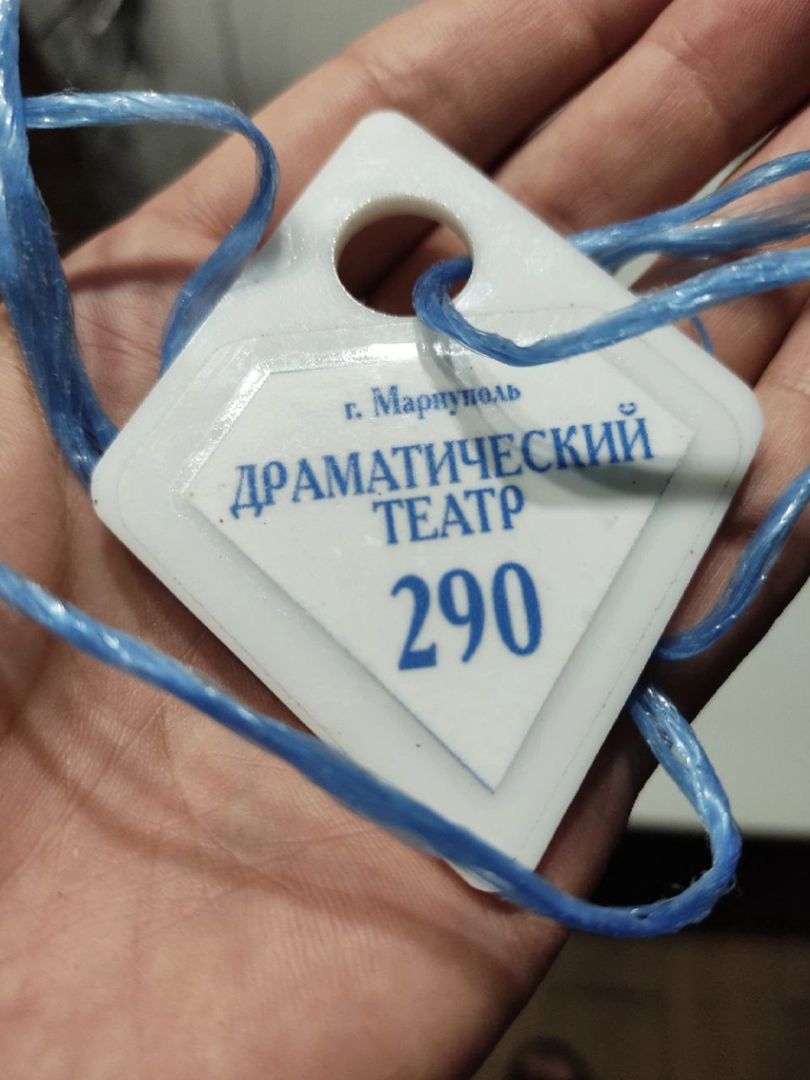

“Well, the audience hall was wrecked in just a few days. It was so sad and excruciating to look at because all of it felt like my own. It was like home. I know how hard our management worked to achieve it all, what kind of red tape it involved, all these renovations and purchases and whatnot,” recalls Yevheniia Zabohonska. For as long as they could, the theater employees tried to keep the building in the same condition as before the war escalated in the hope that the Russian army’s advance would soon stop. The testimonies of the people who sheltered in the theater, supported by photos and footage of the interior, indicated that couches, chairs, seats from the auditorium, stage sets, curtains, and the theater accounting books were used to maintain the functioning of the shelter. Even small elements such as coat check number tags were involved in marking volunteers in the theater—one of the tags has been preserved after evacuation by Ihor Navka.

The volunteers and witnesses in our research informed us that people did not settle in the theater randomly or chaotically. The system was determined, firstly, by the intense bombings of the city and the probability of a missile or bomb hitting the theater, and secondly, by the safety and needs of the more vulnerable population groups.

Since the theater sheltered a high number of children, from toddlers to teenagers, they occupied the potentially better-protected spaces: the witnesses of the attack on the Drama Theater describe that volunteers placed families with children in the bomb shelter and in the rooms with thick walls and no windows. In addition, the dressing rooms behind the scenes were also considered to be safer; these rooms hosted pregnant people and babies. Families with children also lived on the upper floors—once again, with a preference for windowless rooms or rooms with “two walls.” Older adults and people with limited mobility were settled on the first floor.

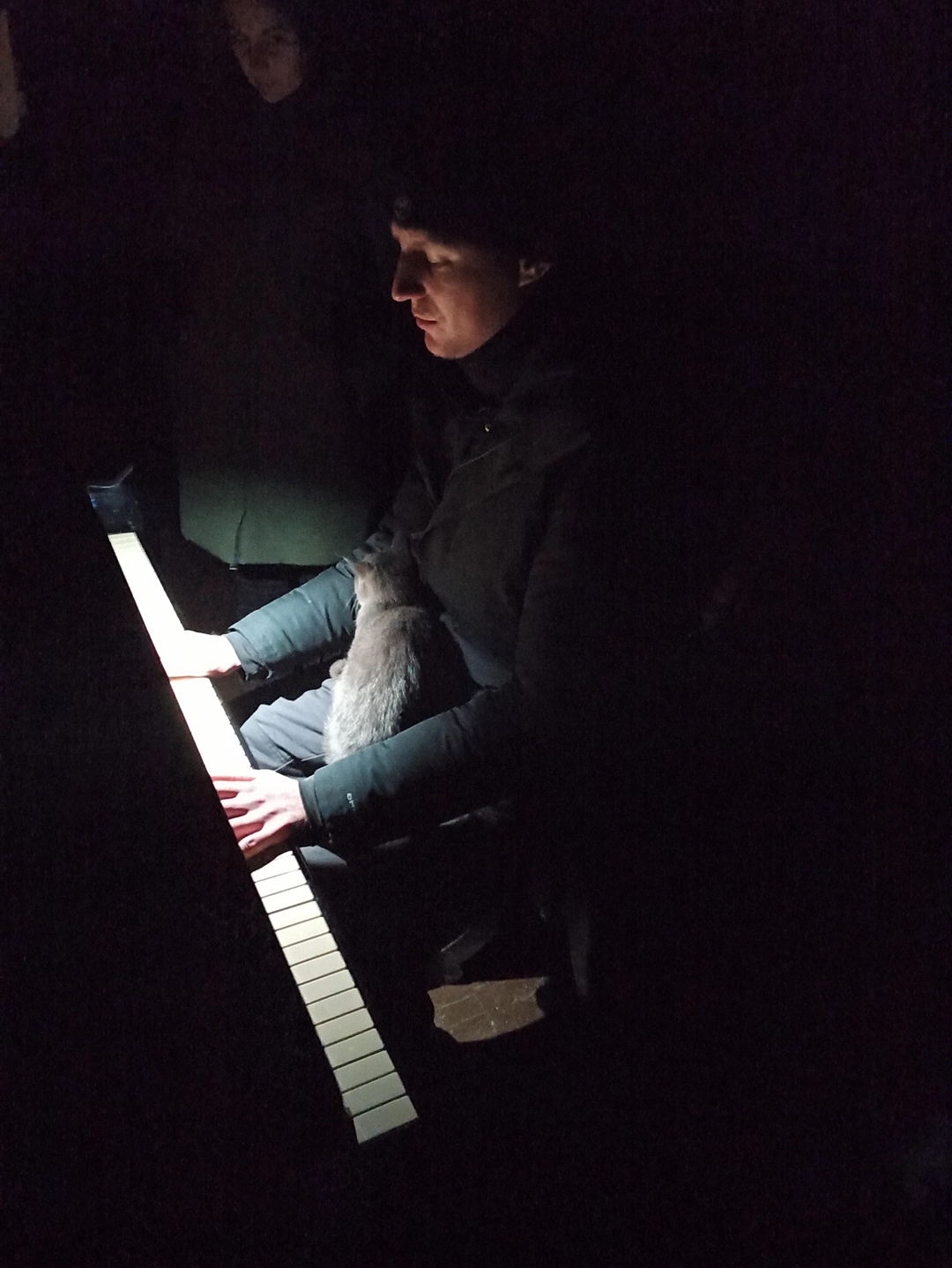

The safest rooms—the bomb shelter, all the rooms and corridors on the first floor (except for the theater hall)—were so crowded that there was barely any room for passageways. In contrast, the theater residents say they avoided the audience hall and the stage as the most dangerous spaces in the theater. However, all the witnesses whom we were able to talk to recall that, at a certain point, they had to cross the theater stage to get somewhere as it was situated in the very center of the theater, functioning as a dangerous crossroad for people searching for toilets, medical assistance, charging points or simply distraction. People came here to play the piano and listen to music: in complete darkness, they lit the instrument’s keyboard with flashlights. Olha Korniichuk, a teacher and a witness to the events, documented one of these moments.

Yelyzaveta Fatieieva, an actress, student, and witness to the attack, described during an interview the anticipation of danger she felt in the auditorium and on stage shortly before the bombing: “I remember the moment when Dima [Dmytro Murantsev] and I went to the stage because we had absolutely nothing to do the whole time. And we sat there, I remember, with a pack of crisps. [...] It was such a terrifying atmosphere, a pitch-dark theater, only some flashlights scattered around the place, ‘cause there were also people there. We sat there, stared at the ceiling, and thought, ‘If there’s a strike right now, we’ll be just completely crushed here.’ [...] We just talked about how this was probably the most dangerous place of all.”

Darkness was one of the critical characteristics of the theater during the city's siege, mentioned by all the witnesses in our study. After some buildings neighboring the theater were bombed, many of the windows were knocked out in the shelter. The volunteers decided to board both damaged and undamaged windows with plywood, so even daylight hardly reached the rooms. Meanwhile, the theater residents invented ways to minimally light the space. Ihor Navka explains: “There was this young guy [...]. We dragged everything we could find in the ruined shops to him. Electronics and whatnot. He’d take LEDs from there, take apart batteries from old laptops, and make these very simple [flashlights]: you close the circuit, it lights up [...]. He gave them out to activists like me so we could have some light. Because it was pitch-dark everywhere.”

A scene from a spatial interview with Ihor Navka. ©Center for Spatial Technologies

On 5–6 March 2022, some volunteers formed a group to ensure minimum levels of safety in the theater. Oleksandr Myronenko, a volunteer and a witness in our study, was among those who joined it. The “guards”, as the Drama Theater residents referred to them, together with other volunteers, among other tasks, were responsible for keeping records of the theater’s population. To make sure that, despite the darkness, they could verify whether someone was in the theater at any given moment. In addition to the safety issue and the necessity of tracking the number of people in the building, this list was also created to ensure that, despite the darkness, people could verify whether someone was in the theater at any given moment. The records, which were crucial evidence of the level of self-organization and the number of people sheltering in the theater, were lost during the attack.

Furniture, plywood, and similar construction materials were also used as protective elements to form special structures near the spaces where people slept or stayed during the day. We were able to model some of these with the witnesses during the situated testimonies.

Spaces of consolidation and interaction

In addition to allocating people and self-organization in the Drama Theater concerned several key needs: food, water supply, and medical treatment. Specially equipped spaces inside the theater and nearby were used for this purpose. However, maintenance of their functionality required more than the community’s internal resources, so an entire network of connections was formed in Mariupol. To maintain the operation of these spaces, volunteers were compelled to frequently be outside with no protection from bombings and shelling. By doing so, they consciously exposed themselves to danger while taking responsibility for the lives of others10.

The witnesses of the attack say that the field kitchen was considered one of the most dangerous places in the Drama Theater. Photos, videos, and eyewitness testimonies indicate it was located outside, to the right of the building. So only 10 to 15 people from the volunteer group cooked here to centralize the process and reduce the risks of leaving the theater for most residents. However, there might not always be enough food for everyone, so people were still forced to go to the field kitchen. In total, there were usually 50-70 people there.

The organization of the field kitchen was among the most challenging tasks. At first, it was hard to cook for several thousand people without gas or electricity on makeshift bonfires. The majority of the residents cooked their own food independently, but as early as 6 March 2022, the owner of “One Gogi,” a restaurant located in the Theater Square near the Drama Theater, allowed the volunteers to use the restaurant’s kitchen equipment, freezers, and the leftover food supplies11. Then, on 8 March 2022, the police brought special field kitchen equipment to the theater. Yevheniia Zabohonska recalls: “We came up to the police, they asked what we’re missing, and we said we need a field kitchen. Two hours later, we had a field kitchen. I can’t even tell you how happy our cook, Misha, was. I still remember it. He was literally glowing. He planned everything right then and there: today we cook this, tomorrow that.”

Based on eyewitness testimonies, photos, and videos, we have recreated the organization of the space around the theater’s field kitchen. Our reconstruction demonstrates that a vital kitchen component was a protective structure built from materials at hand. Vitalii Tsesar, a volunteer, resident of Mariupol, and driver, who maintained the functioning of the field kitchen along with the others, describes: “Then we filled everything with wooden pallets. So that they’re not shot through [...] by shrapnel, and [so that] they can’t see us. [...] And water was stored there for safety purposes, so that [...] we’re [not] hit by shrapnel. If there’s an explosion nearby, the barrels with water would save us.”

The volunteers who cooked disinfected their hands with antiseptics to maintain hygiene because the sanitary conditions in the theater were invariably difficult due to limited access to drinking water. People did not have the opportunity to wash themselves, as there was barely enough water to clean toilets, drink, and cook. They tried to maintain hygiene using antiseptics and wet wipes, but these items were scarce and often only available to parents with babies.

The wooden elements of the seats in the audience room of the theater were used as firewood for the field kitchen. But these were not enough for such a large number of people that were served by the field kitchen, so wooden structures from the open-air ice skating rink behind the theater were also used. “We came up to the police and said, ‘We need firewood for the kitchen. [...] there are planks over there at the ice skating rink, the pretty fencing, can we take it?’ He [the police officer said]: ‘Yes, take it all,’” recalls Ihor Navka, one of the volunteers who, in addition to looking for firewood12.

The functioning of the field kitchen and the theater as a shelter, in general, would have been impossible without support from the municipal services and the military. The witnesses of the attack on the Drama Theater who lived in the shelter report that the major shelters in the city formed a kind of network during the siege, in which volunteers, the police, and the military maintained connections. In addition to the equipment required for the field kitchen, they brought food from large warehouses13, water, warm clothes, medicines, and other basic necessities to the theater. At the same time, various testimonies confirm that the military never entered the building and only stayed outside to avoid endangering those who were taking shelter inside14.

Even though the military, municipal services and volunteers were able to build a food distribution system, it was still difficult to feed several thousand people. The volunteers used all the available resources and even managed to set up a bread-baking process without power, water, or gas supply. However, there was not enough food for everyone: they could often only feed the children. Mariupol resident Viktoriia Dubovytska told us a lot about the lack of food in the theater and about how hard it was for her children to experience: “My kids started crying and saying, ‘We’re hungry.’ And he [a man whom Viktoriia met at the theater] went out in the evening and brought them like half a dozen frozen sausages. Well, their quality was, of course, so bad that they were impossible to eat. Only give them to the dog. And he brought them. And we put those sausages like this in a cup [of hot water] to defrost them.”

A map of the network of connections between the theater's food-related areas. ©Center for Spatial Technologies

For extended food storage, volunteers utilized an additionally equipped basement space in the theater, separate from the bomb shelter. They also used freezers from “One Gogi” cafe, slightly powered by a generator supplied by the police.

The municipal company Mariupolvodokanal, the Emergency Service, and the police supplied water to the theater to the extent possible. However, it was still not enough due to the lack of a centralized water supply. To provide several thousand people with water, those hiding in the theater had to drink water from a utility well near the field kitchen, intended for watering plants and cleaning the streets. Witness Viktoria Dubovytska recalls: “We collected that water, again, as just drinking water. We boiled it and sort of used it for the bathroom. When it was boiled, we looked inside a plastic cup [...] [, and] there was this much sediment at the bottom [points at the level of half of the cup]. The water was still gray, but what can you do? There’s no other water. So we drank this one.” Due to the lack of water, the theater residents were very frugal about its use. Viktoria reported that because she was used to keeping water for the kids, she was wary of drinking even some time after the evacuation: “My husband and I were riding the train. And I look at water like this: I’m thirsty. I look at water, [but] I can’t even touch it, I can’t drink it. It was so ingrained in my head that I can’t drink water ‘cause the water’s for the kids, ‘cause they need it more.”

Due to the consumption of unprocessed water, spoiled food, and low temperatures, many people were ill with COVID-19, pneumonia, and food poisoning in most rooms in the theater. “There was a lot of coughing, sickness, and so on. [...] babies literally kept crying all the time,” recalls Dmytro Murantsev. Meanwhile, injured people were arriving at the theater, so the volunteer group organized a medical station on the first floor in one of the dressing rooms. It was equipped to receive patients, provide first aid, and store medicine. The patients were examined and treated by nurse Olena Matiushyna, one of the few people in the theater with medical training.

Just like food, medicine was also distributed between bomb shelters in the city. Already in early March 2022, it was incredibly difficult to find medicine. As hospitals were being bombed15, establishing a medical station in the theater became necessary. City residents, together with the police and municipal services, would sometimes visit warehouses and pharmacies in search of medicine—at times, they were able to find strong painkillers or antibiotics for the seriously ill.

Writings outside: “ДЕТИ”

On 14 March 2022, satellite imaging captured two inscriptions that read “ДЕТИ” (“CHILDREN”) in Russian outside the square—next to the main facade and the back of the theater. Its residents decided to do it to inform the Russian army, who were bombing the city using military jets that the theater was serving as a shelter for civilians. The writings became a symbol of the war crime.

An anonymous witness sheltering at the theater with her child recalls: “I [...] wanted them to see it from above because the plane kept circling. We were so scared of it [...], [because the theater] was very visible, it’s in the city center after all. [...] When there was war in Syria, I saw a video about how the only place that wasn’t touched was a school. Lots of kids were gathered there, and they wrote ‘Kids’ in front of the school. And it was the one school that nobody touched. So everyone there survived. I thought it would help16.”

Meanwhile, another witness, Viktoria Dubovytska, who was at the theater with her two children, said that opinions during the discussion were divided: some people believed that the writing would lead to the opposite of what they intended, a purposeful attack on a civilian shelter.

***

Both the difficult humanitarian situation in the Drama Theater during the siege of Mariupol and the bombing of the shelter by the Russian army on 16 March 2022 cannot be separated from the general tactic of urbicide employed against Mariupol. This systematic destruction was aimed not only to erase the city’s architecture but also the social ties that permeated the urban fabric. This assault became one of the symbolically pivotal acts of terror against Mariupol, but at the same time, it was not the only one and not the last. In the recollections of witnesses, the theater bombing is echoing past crimes of Russian imperialism, with the same perpetrators still unpunished.

As the city faced relentless shelling and infrastructure destruction, over 2,000 people sought refuge in the theater. Having found shelter here, they tried to at least temporarily replace their destroyed apartments and houses with curtains, stage scenery, and other improvised materials. Moreover, they endeavored to at least minimally adjust the water distribution systems, food supply, and medical care. The efforts and practices of self-organization and protection of people saved most of the building’s residents from shelling in the city and even from the effects of a direct air strike.

The theater architecture merged with the collective efforts of its communities and eventually, as a result of numerous bombings, transformed into a media imprint—an array of photos, videos, and fragments of testimonies online. It is irrefutable proof of the Russian army’s crime against this city. Carved out in the Mariupol landscape through the experience of tragedy and resistance, this imprint will be impossible to erase or hide.

We have researched and documented the events leading up to and following the theater bombing, detailed in the subsequent text.

Text written by Ksenia Rybak

Translated by Roksolana Mashkova and Viktoriia Pushyna

Edited by Nychka Lishchynska

Visual materials and research by: The Center for Spatial Technologies

References

Kariakina, A. (2023). Mariupol. Maternity hospital. “It was as if the entire planet exploded” (Маріуполь, пологовий. «Ніби вся планета вибухнула»). In: N. Humeniuk (ed.) The Most Horrifying Days of My Life (Найстрашніші дні мого життя). The Reckoning Project reports. Lviv: Choven, 2023. Pp. 113–127.

Ukrainian Healthcare Centre (2022). Destruction of Healthcare in Mariupol. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1tJyyae_9eBF_IfkPiDb5i9D2Bqb-2n5w/view

Coward, M. (2009). Urbicide. The politics of urban destruction. New York: Routledge. Pp. 35–54.